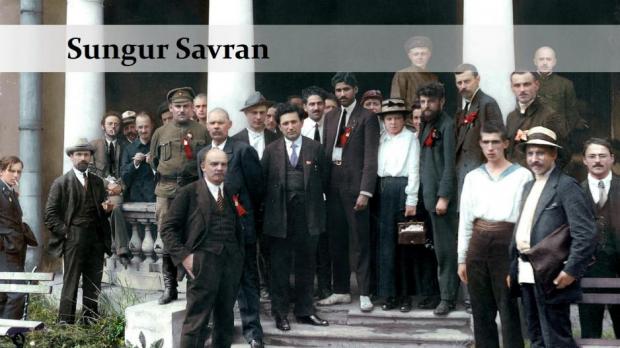

Second Congress of the Communist International (1920): Lenin, with Maxim Gorky right behind him, on whose side are, respectively, Zinoviev, the President of the Comintern, M. N. Roy, delegate of India, one of Lenin's sisters, and on the left, sitting on the balustrade, Karl Radek, with Nicolai Bukharin standing right next to him. The Second Congress is of immense importance for Lenin's legacy.

We are gathered here from five continents on the centenary of Lenin’s death in order to discuss his legacy, because we are interested more in the future than in the past or, rather, we are interested in this past to the extent that it teaches us about the future. That is why Lenin’s legacy means so much to us and we wish to discuss it.

And yet this legacy is ingenuously misunderstood or deliberately denied or surreptitiously rejected. By this I do not mean the overall immense contribution he made to the Marxist programme, strategy, method of organisation, in particular of the revolutionary party, and theory. Lenin’s revolutionary practice from the Great War on, that is during his last decade (1914-1924), gave rise to an entirely original programmatic and strategic vision for the advance of world revolution. It is this strategic vision that has been ignored or denied for the last one hundred years.

Today I am going to dwell on a single area, the apex of his internationalist vision. I call this the “question of nations”, not the “national question”, as this area of Lenin’s thinking and practice is commonly called. I do this purposely and it will become clear in the course of my speech why I make this special choice.

Why do I dwell on this alone? For several reasons. First, it is an area which has been underestimated immensely. Remember, when I say this, I am not talking of the “national question”. That has been discussed widely. But not the “question of nations” that I will be taking up in this speech.

The second reason is this: This is the area in which Lenin stands out as the major spokesperson of world revolution in the 20th century, as opposed to national-communism. And because the major reason of the collapse of the experiment of socialist construction and of the workers’ states in the 20th century is the failure of communism to address the question of world revolution in the proper manner, because international communism was betrayed by many in the movement, starting with the Soviet bureaucracy, this polarisation between world revolution and internationalism, on the one hand, and socialism in one country and national-communism on the other, is the most vital problem to be overcome for future socialism, socialism in the 21st century. And, for a second time, Lenin has the answers to what is to be done. Lenin’s legacy provides a program, a strategy, and a method, in addition to the conception of the party and the International, for future socialism.

Third, this vision is not understood, not grasped by even Lenin’s most loyal followers and the best elements of the revolutionary Marxist movement worldwide. Neither Lenin’s practical struggle to shape the Soviet Union in the way that it finally took form nor Lenin’s practice in winning the entire Russian East, in particular the Muslim peoples of the Tsarist empire, nor yet his vision for the future World Socialist Republic have been really appreciated to the full up until today.

The “question of nations”

What, then, is the “question of nations” that I am talking about? This question is not co-extensive with the “national question” that has been debated endlessly. It includes but cannot be reduced to that question. The famous “national question” that everyone recognizes was an integral part of the Bolsheviks’ programme thanks to Lenin’s interminable efforts is only one element in the much larger “question of nations” that I wish to speak on.

To compare and contrast the two, i.e. the “national question” and the “question of nations”. The first is predominantly, but not exclusively, related to the policies communists need to pursue with regard to the relations between an oppressor nation and an oppressed nation. This question is usually associated with the right of nations to self-determination. And it is very commonly presented as a “democratic question”, that is to say, one that is not related to socialism or communism, but simply with a “democratic right”. In this sense, its status in Marxist thinking can be compared to the status of political and civil rights or the right to the freedom of association of the working class in unions and the right to strike.

The “question of nations” is something much more extensive and is definitely not a “democratic question” but one that is directly related to socialism and communism. Its import is not limited to the tactical question of how to handle relations between nations in a democratic manner until the socialist revolution comes along and solves the national question. On the contrary, after the 1914 watershed of World War I and the utter betrayal of the Kautskys and the Eberts, of the Longuets and the Plekhanovs, Lenin now reflects on the set of questions posed by the multitude of nations in the world as a problem for the construction of socialism and a barrier to be handled attentively and tactfully on the road to communism.

Lenin now poses an entirely new question in the history of the communist movement. For Marx and Engels, the necessity of Irish liberation was a condition of the socialist revolution. As long as the Irish nation was subordinated to the English, the working class would remain divided along national lines. This was also the basis of Lenin’s persistent emphasis of the “national question” until 1914, fighting as the Bolshevik Party was in a notorious “prison of nations” that Tsarist Russia was. But now, after 1914, Lenin is reflecting on a totally different question: in a world divided into nations with contradictory, even hostile interests, how will the dictatorship of the proletariat overcome and transcend the contradictions between this multitude of nations?

This, then, is the question of nations. This question is not related to a “democratic right” but to the construction of socialism in the period of transition between capitalist society and classless society. Furthermore, it is not a tactical question that may be solved through different methods in different national contexts. It is a strategic question that the entire communist programme is predicated upon.

This is the question that I will discuss. Since our time is limited, let us now immediately pass on to the answers that Lenin brought to this very complex and burdensome question.

I. Political programme to solve the “national question”

The political programme that Lenin formulated for the solution of the traditional “national question” continues to be part of this new strategic vision. The programme in question can be summarised under three headings:

- The right of nations to self-determination: This is a continuation of the earlier democratic and tactical measure of unifying the working class of each country or region or wider geography. This right provides for oppressed nations the guarantee that the proletariat of what was earlier the oppressor nation, i.e. the Russians after 1917, the Serbs after 1944, the Han nationality after 1949, etc. does not intend to carry on the oppression implemented by its bourgeoisie against oppressed nations so that the 0united effort of the proletariat of the oppressor nation and of the oppressed nations and nationalities is worthwhile pursuing for the oppressed nations as well in trying to reach together a classless society.

- The federal principle: Lenin was, until the very end, a fervent partisan of economic unification at the highest level possible. That is why before the revolution he was against federalism. However, having experienced the persisting chauvinism of the oppressor nation even in the ranks of the proletariat and its vanguard, he quickly turned towards federalism, all the while insisting on economic centralism. The federal principle was also buttressed by and integrated with the right to self-determination.

- Real equality between nations, beyond formal equality: Lenin insisted that formal equality between oppressor and oppressed nations was at best a petty-bourgeois perspective that would, in the final analysis, sink to the level of a bourgeois position, just as formal equality before the law was a bourgeois principle that could co-exist with gigantic socio-economic inequality between classes. So, he defended what is today dubbed “positive discrimination” (British) or “affirmative action” (US) in favour of the oppressed nations.

II. Strategy and tactics in revolutionary practice

The strategy that Lenin pursued in his practice within the land of the soviets, a strategy that he defended in the face of resistance from very different quarters within the Bolshevik Party, but with the full support of Trotsky, was in complete harmony with this programmatic orientation.

- Peaceable granting to five nations of the right to self-determination: Finland, the three Baltic states (Estonia, Lithuania, and Latvia) and somewhat more controversially Poland were granted independence as a practical sign and confirmation of the new Soviet government’s commitment to the right to self-determination.

- Extreme respect toward the specific national and religious sensibilities of the Eastern peoples within the former Tsarist empire: This was instrumental for winning them over to the Soviet regime, despite the fact that only a handful of these peoples possessed a modicum of the modern proletariat in their class structure.

- The foundation of the Soviet Union on egalitarian bases: This means fundamentally equal terms for the major nations and an honourably autonomous basis for the smaller nations and no privileges for the Russian dominant nation. As Lenin was struggling against a deteriorating health condition, Stalin and his co-thinkers in the Commissariat of National Issues were developing a project for unifying the existing Soviet governments in different corners of former Tsarist Russia (e.g. Russia, Ukraine, Belarus, Armenia, Georgia, Azerbaijan etc.) on the basis of a project called “autonomisation”. This meant that all other nations would join the already established Russian Socialist Federative Soviet Republic (RSFSR) as autonomous republics, on a par with, for instance, Bashkordistan or Daghestan, these being smaller nations that were sub-units of the Russian heartland. Lenin fought tooth and nail against this and had his own project of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics win the day, which established equality between the larger national groups in Soviet territory. It is in this context that Lenin dictated to his secretaries the “Question of Nationalities or ‘Autonomisation’”, written against Stalin and his cohort, the most powerful of his texts defending real equality between nations as opposed to formal inequality and therefore advocated “positive discrimination”.

- “Korenizatsiya”: Not only these major nations of what was earlier Tsarist Russia, but also down to the smallest nations and nationalities of Russia proper were granted the right of ruling their own federative unit within the federal republic on the active participation of their people, learning and using their own language alongside Russian, the federal language of communication, and mobilising their people’s forces in order to create a national renaissance after decades, sometimes centuries, of servitude under the Tsarist regime.

This is the solid bedrock on which rose the amazing national structure of the Soviet Union, one that not even the national-communism and the creeping Russian nationalism that the bureaucracy fanned over the decades could undo totally. This is the precedent also for decades of successful implementation of an egalitarian national policy in other multinational socialist countries such as Yugoslavia.

III. Unique national character of the USSR

The result of Lenin’s single-minded insistence on the freedom of nations to secede and on the importance of real equality, rather than formal, was the creation of a state that was unlike any others in the modern age. The USSR stands out as a unique case of a state in the annals of state-building in the entire modern age.

Perhaps many of you have noticed the use of an unusual term “state-building” rather than the usual “nation-building” utilised by US official and intellectual circles. This is obviously on purpose. For, to pose the matter in its most naked form, let us put forth the following question: in the age of nation-states, which nation does this state belong to? What is the answer to this question? Total silence. There is no nation involved here! For the first time in modern history, we have a state which does not carry in its appellation the name of a nation or even of a geographic space, such as the United States of America. (Let us not forget, by the way, that “America” has become veritably the name of a nation.) The USSR is a nationless state. If, then, as Lenin believed, the period of transition to socialism must overcome and leave behind all national divisions, the USSR, in form, but not yet in substance, has already started the trajectory towards that supersession, that aufhebung of nations.

At the antipode of this nationless political entity lie the federative units, the autonomous regions and the autonomous republics and the Soviet republics of the self-same state structure. These are units that give life to the earlier dying nationalities, languages, and cultures of Tsarist Russia, which, now, find the best of conditions to revive those nations and nationalities.

What is this contradiction at the heart of the Leninist conception of the transitional state? Why a nationless state with sub-units that are filled with nation-building zeal and korenizatsiya? This contradiction is a dialectical one in the best sense of the word. The national revival and korenizatsiya policy, at the extreme opposite of the nationless federal state, is in fact exactly the embodiment of the principle of real equality as opposed to formal equality that Lenin defends. For nations to be equal not only formally but in real terms, what is needed, we have already seen, is “positive discrimination”. Well, here is a situation where one nation, the historically oppressor nation, the Russian nation, in other words, is, so to speak, arrested in its development, while all the others are given the green light to advance their national revival and awareness as well as self-rule. Can one think of any better way to fight not for formal, but for real equality?

IV. Strategic vision for the international arena

Up until this point we have established two major points: First, Lenin’s approach to the relations between nations in the period of the dictatorship of the proletariat imputed an entirely new meaning to this question never before discussed by Marxists (Section I above). Second, this new perspective was translated into his revolutionary practice in very different ways in relation to the construction of the new Soviet state (Parts II and III). Now we are going to complete the picture by projecting Lenin’s approach from the domestic “question of nations” within the Soviet Union onto the international arena. Out of many different aspects, we will highlight four points in this area.

- The Comintern and the internationalisation of Bolshevism on the national question: The Communist International (Comintern) was the environment in which the revolutionary organisational and political outlook of the Bolshevik Party was transmitted gradually to the new communist parties in other countries. (Towards the end of his life, Lenin thought this was overdone, but that is for another occasion.) Concerning the “question of nations”, Condition # 8 among the “21 Conditions” for joining the Communist International is of paramount importance. Social democratic parties, members of the Second International, were soft on imperialist colonialism, some wings even defending imperialism on the excuse that it brought civilisation and progress to “primitive” peoples. So, Condition # 8 set a strict principle for the Communist Parties of imperialist countries: they were duty-bound to fight the imperialist policies of their own state and military and stand in solidarity with the oppressed nations of colonies in deeds, not only in words.

- Unity between anti-imperialist emancipation and socialist revolution: The obverse side of the duties of Communist Parties of imperialist countries is the orientation Lenin advocates for peasant countries. On the basis of the revolutionary struggles in the Middle East and China before and after the Great War, Lenin came to believe that peasant countries may directly move towards sovietisation under the hegemony of the dictatorship of the proletariat established in Russia. Despite all that later occurred in the Soviet Union, this is indeed how revolution advanced in the 20th century.

- The strategic vision regarding transition towards a World Socialist Republic: The vision that towers over all the other policies implemented, but unfortunately has remained in the shadow up until now is the strategy devised by Lenin for the transition from dictatorship of the proletariat in one or several countries toward a World Socialist Republic. Lenin would probably have condemned as national-communism the establishment of socialist governments on a national basis in each country that achieved revolutionary victory, the road taken universally after World War II. His strategic vision is embodied in the rightly famous “Theses on the National and Colonial Questions”, drafted by him, reviewed in the relevant commission twice, and voted almost unanimously, with three abstentions, by the general assembly of the Second Congress of the Communist International in 1920. In its theses # 6 to 8, this resolution stipulates the unification of new socialist states with the Soviet Union under the transitional form of a federation with, among others, the aim “to create a unified world economy according to a common plan regulated by the proletariat of all nations.”

- The sovietisation of peasant countries and their joining the federation: This is not only true for countries with a developed capitalist class structure, but also peasant countries. Of course, Lenin warns that each case should be assessed on the basis of its merits, but insists that no former colony can hope to develop in a manner that will liberate its economy from the reign of imperialism. He castigates the imperialist bourgeoisie because “under the mask of politically independents states, they bring into being state structures that are economically, financially and militarily completely dependent on them.” So, the objective should be “wherever possible to organize the peasants and all victims of exploitation in soviets and thus bring about as close a link as possible between the Western European Communist proletariat and the revolutionary movement of peasants in the East, in the colonies and in the backward countries.”

Conclusion

In the light of what has already been said, we can conclude without any hesitation that the programme and the strategic vision advanced by Lenin in the last years of his life defined a path for communism entirely different from, indeed diametrically opposite to, that taken by the leaderships of the communist parties that took power in and after World War II. Lenin’s vision is entirely different from the later leaderships in that it is internationalist through and through.

What can we conclude about the later leaderships then? I am not going to go into a detailed analysis of why the 20th century experience of socialist construction failed so miserably nor pass a judgment on the post-Lenin leadership of the Soviet Union or the leaderships of other countries that experienced revolutions later. The only thing I will say is this: it is on the rocks of national-communism and socialism in one country that the 20th century experience shipwrecked.

Imagine for a moment: If Stalin and Mao, Ho Chi-Minh and Tito and all the others had been loyal disciples of Lenin, one single socialist federation could have been formed by the early 1950s extending from Central Europe in the west to the East China Sea and the Yellow Sea in the east and from the Arctic Ocean in the north to the Mediterranean and the Pacific Ocean in the south. Can you imagine one single socialist federation including the country with the largest territory on earth (the USSR) and the country with the highest population in the world (China)? What opportunities would that have created with respect to economies of scale and judicious and equitable division of labour and scientific and technical cooperation and how fast a growth plus industrialisation pace would have been achieved! And how strong, militarily speaking, such a state would have become vis-à-vis imperialism! And on top of that, given what Lenin envisaged with respect to peasant societies becoming sovietised, imagine additionally, for the sake of argument, that India joined this socialist commonwealth even if after the Partition. Then the second country with the highest population in the world would have become part of this federation also and the boundaries of the socialist commonwealth would have reached the Indian Ocean as well. Capitalist restoration would probably have been postponed by many decades.

Lenin, then, is the alternative of the future, the one not yet tried.