Süleymaniye is not a mosque.

Nâzım Hikmet

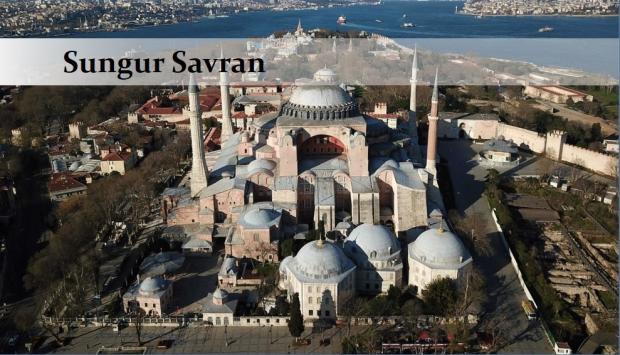

Nâzım Hikmet, the Turkish poet who sang the praise of the October revolution, wrote thus, under the pen name Orhan Selim, in a column he was writing for a daily newspaper in the 1930s. He was considered too dangerous as a communist poet and militant to be able to write comfortably without fear of constant censorship and harassment under his own name and that is why he adopted a pseudonym. The “Süleymaniye” he was talking about in the article from which we are quoting is very palpably a mosque, situated on a hill of Istanbul. It is in fact the chef d’oeuvre of the world-renowned Ottoman architect Sinan (d. 1588), commissioned by that other historic figure, Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent or Lawmaker (1520-1566), now made, through an irony of history, more famous internationally than ever because of the popular television series called “Magnificent Century” exported to all corners of the world. What Nâzım was saying, against the fact and against common sense, was that Süleymaniye was such a beautiful building, such an extraordinary creation of the human mind and of human technique, such a magnificent product of the genius of Sinan and the skillfulness of his masters, that it is first and foremost a work of art in itself and only secondarily and contingently a religious abode.

This is also true for that other wonder in the same city of Constantinople called Hagia Sophia.

The conquest of Istanbul

The taking of Istanbul by the armies of that other world-renowned Ottoman sultan Mehmed II alias the Conqueror was an epoch-making act of diplomacy and war. It implied that a new empire was being born of the ashes of what had for ages been first Eastern Rome and later Byzantium, mighty empires themselves. It changed the physiognomy of both Europe and the geography that is now commonly called MENA (the Middle East and North Africa) because it made the Ottomans a part of what was much later to be called the “Concert of Europe”, an actor in the shaping of Europe’s destiny, at once an actor in the predominantly Judeo-Christian world of the continent as well as a Muslim other that was constantly theeatening that world, and later, in the 19th century, “the sick man of Europe”. The Ottomans had, of course, penetrated the Balkans earlier, but “Empire” they became once that jewel of a city, Constantinople/Istanbul (“Konstantiniyye” among the Muslims) was conquered.

Constantinople was taken by the Muslims, but the memory of Rome (Eastern Rome, of course) hovered over the territory that was then called Asia Minor and is now called Anatolia. In Turkish, the Greek population that remained behind after the fall of Constantinople in Istanbul, Anatolia and even offshore Cyprus, Crete and the other islands in the Aegean Sea came to be called and is still called not Yunan, the word used for the Greeks of Greece, but Rum, meaning obviously “of Rome”. The Rum population are unfortunately mostly gone, but the name remains. This is so true that the poet that is probably considered the greatest poet of this same geography until Nâzım came along, a Sufi poet of the 13th century, is also called Mawlana Jalaleddin Rumi, (“one who belongs to Rome”)!

So although the Ottoman Empire was decidedly an Islamic state (the sultan became, somewhat later in the early 16th century, also the Caliph of all Muslims and remained so all the way to 1924), the society it gave birth to was a unique mixture, an amalgam one is tempted to say, of what are now considered to be the Orient and the Occident, isolated from each other irretrievably as it were.

The Ottomans were ferocious in their treatment of Constantinople and its population. However, everywhere from Mexico City to the Ayodhya Temple/Babri Mosque in India, conquerors either razed the temples of the previous civilisation to the ground and built their own place of worship upon the debris or converted the same building to be used as the religious abode of the conqueror. This is what Mehmed II the Conqueror did to Hagia Sophia, built in the 6th century and used as a cathedral. He turned it into a mosque without, however, destroying any of the artwork and belongings precious to Orthodox Christianity. He was for a synthesis of East and West, but of course under the iron fist of his own civilisation. The conquest of Constantinople was also a very violent affair, with incidents of mass killings, pillage and enslavement. But again what civilisation did not commit the same acts of what we now consider to be inhumanity? Al Quds/Jerusalem, that city considered sacred by all three monotheistic religions, was once almost bled to death by the conquering armies of Crusaders. And Haghia Sophia itself had earlier been transformed from an Orthodox basilica to a Roman Catholic cathedral under star of the same lineage of the Crusades.

Today the government of Erdoğan and the Council of State, by a strange twist of history that very typically Western (French) institution that was imported in the epoch of “Westernisation” of the Ottomans in the 19th century, together have turned Haghia Sophia into a mosque. But was it not a mosque already since the conquest and has it really been turned into a mosque? To answer these questions, we have to understand the second conquest of Istanbul.

The Dardanelles impassable?

Istanbul/Constantinople was lost to the Turks, at least temporarily, at the end of the Great War. Allied troops occupied the city unofficially on 13th November 1918 immediately after the signing of the armistice with the Ottoman state. Later on 16th March 1920 the British would re-occupy the city, this time officially, closing down the fragile Ottoman parliament and entrusting the administration of the country to the weakling called Sultan Vahideddin, who had been enthroned towards the end of the war, and a certain Damat Ferit Pasha (“damat” meaning “son-in-law” because he had married a lady of the Ottoman court), a lackey of British imperialism, as the Premier. In between, on 15th May 1919, the Greek army had landed in Izmir (Smyrna, today the third biggest city of the country, an important port city on the Aegean since the 19th century) at the behest of the British.

Even today the average Turk will make a big thing of the fact that the British and allied forces were repelled in the so-called Dardanelles campaign of 1915, during which the Allies tried to cross the Dardanelles Strait in order to reach Istanbul and gain control also of the Istanbul Strait (the Bosphorus) opening up to the Black Sea, (popularly summarised in the brief expression “Dardanelles impassable”, so popular that it is commonplace even in football fans’ jargon). However, as soon as the war was over the Dardanelles had been, figuratively speaking, crossed and both straits had come under British rule. The battle of Dardanelles was won, but the war for Istanbul and also Anatolia was lost. Even the rump state that was left behind after the Ottoman state parted with its Balkan possessions in the Balkan Wars of 1912-1913 and its entire possessions in Mesopotamia, the Levant, and the Arabian Peninsula during the Great War, now lost control of a good part of its territory to the occupying forces of imperialist countries (Britain, France, Italy) and of the British protegé that was the bourgeois kingdom of Greece of the time.

The Ottoman empire was moribund, but delivered most of its territory to imperialism and its allies willingly for the sultan and the camarilla around Damat Ferit were trying to save their own skin by surrendering to the British. Had the entire Turco-Muslim population of Anatolia not begun to organise in local associations and even to fight the occupation in the different regions through guerrilla warfare and had the remaining cadres of the previous bourgeois revolution of 1908 not organised and centralised these at times centrifugal local forces to establish a base for dual power in Ankara and built an army that could cope with the occupiers, Western Anatolia might very well have been Greek territory for the rest of the Twentieth Century. All of this was necessary, but not sufficient. It was the existence of Soviet Russia and its alliance with the new government of Ankara established in April 1920 that sealed the fate of Anatolia. Without generous Soviet aid and assistance and without the heroic policy of revolutionary defeatism on the part of the Greek Communist Party, a factor that was significantly influential in the decisive stages of the Greco-Turkish war, modern Turkey might not have survived. The same process through which the army of Mustafa Kemal (later to be named Atatürk) defeated the Greek army and established an independent Turkish state over almost the entire Anatolian plateau also brought revolutionary change from a multinational Islamic empire to a bourgeois republic. Istanbul was thus conquered by the Turks a second time, this time from British imperialism abetted by the Allies.

Without understanding the utter historic failure of the Ottoman Empire, once the standard-bearer of Islamic splendour in Europe, but a pariah in the “Concert of States” in the 19th and early 20th centuries, one can make no sense of the trajectory of 20th century Turkey. The Ottoman Empire had exhausted all its possibilities. The republic was born from the decaying empire. And it was the product of a revolutionary age that lasted for 15 years, marked by wars in between, and two distinct revolutions, that of 1908 and 1923. Those who nostalgically yearn for the empire today are simply ignoring the facts. Hence, the idiosyncratic secularism of the new republic is what explains the fact that Hagia Sophia, a mosque from 1453 on, had to be turned into a mosque once again in 2020.

It was in 1934 that the government of the young republic of Turkey, Atatürk at its head, signed a decree turning Hagia Sophia from a mosque into a museum. In the extremely divided ideological climate of today, when Islamists and Kemalists face each other almost on every societal and cultural issue, the Kemalists interpret this act as a move to strengthen the secular nature of the new state. There is no doubt an element of truth in this, since Mustafa Kemal was trying by all means to reduce the influence of Islam in society and polity. However, this effort to reduce the hold of Islam was not solely for purposes of strengthening secularism. It was very markedly an effort, at the same time, to remould Turkish society as a member of “contemporary civilisation”, which for the Kemalists was imperialist European civilisation in its totality. In other words, the Kemalists were like European colonisers in Turkish skin, self-colonisers one might say. The transformation of the Hagia Sophia into a museum was also a move to make the “new Turkey” sympathetic to European or more generally Western audiences. This, coupled with Turkey’s slavish submission to the US, NATO, and the EU in the period after World War II, did immense harm to the idea of the republic, gained it (and secularism) the enmity of entire swathes of the population, led to the resurgence of Islam in Turkish political life after the 1960s, and is the fundamental historical factor that has kept Erdoğan in power for close to two decades now, as we have explained at length in another article.[1]

Has Erdoğan totally abandoned the terrain of this idiosyncratic secularism? That may very well be the direction he is headed towards. But this is simply a tactical question in that strategic trajectory that he has set himself. This strategic goal is to make Turkey the hegemonic force in the Sunni İslamic world, to start with the Sunni Arab world of the MENA region, and become himself the leader (the rais) of this world. This is the policy of what many have called neo-Ottomanism and what we have called Rabiism in other articles. The culmination of this journey would certainly be the resuscitation of the Caliphate. That would be the seal put upon the recreation of Turkish hegemony over the Islamic world, but is only the supreme form of this hegemony among other possible forms.

Erdoğan may be headed in that direction, but he is very far away from the destination (and it is very doubtful whether he can ever reach that destination). And as long as he has not reached the last lap of this marathon-like race, he will not and indeed cannot abandon Turkey’s closely knit web of ties to Western imperialism. If he can find a sponsor for this goal in the West (for instance Britain, which is now supporting his Rabiist politics in Syria and Libya, or the US, together with Israel, which looks benevolently to a Sunni sectarian policy as long as it fits its struggle against Iran), he will definitely not shy away from such an alliance. So every move that seems as if it were “finally” a break from the past is only another step towards his strategic goal but not a rupture. “Neo-Ottomanism” as a concept, therefore, is misleading. If he can reach his goal under the republican form that will not bother him in the least.

That is why the question of Hagia Sophia being turned into a mosque is itself doubtful. Nowhere has Erdoğan said that it has been “turned into a mosque”. He has only said that the Hagia Sophia will serve Muslims for prayers, hastening to add that it will be open to Muslim and non-Muslim alike. The final setup is shrouded in well-studied mystery. To his devout Muslim audiences within and outside Turkey (remember he wishes to be rais, i.e. leader to all Muslims, at least the Sunni brand), he acts as if the Hagia Sophia were now a mosque. For the consumption of the Christian world, in which the imperialist forces play the major part, he adds “Muslim and non-Muslim alike”. We will see how the content of this duplicitous move on the world and domestic chessboard will turn out in the near future. But for the moment the “mosque” is really no more than a mask.

The final conquest

Not in vain has there been so much suffering Istanbul

Wait for us

Wait for us with your grand and tranquil Süleymaniye

With you parks your bridges your towers your squares

…

Wait for our marches on your avenues with songs of victory

Wait so that the dynamite of history

Wait so that our fists

Bring down the reign of the brigands

Wait, Istanbul, for those days, wait

We deserve you.

Vedat Türkali

Only a month ago we published on this web site an article describing the insurrection of the working class, in Istanbul and the surrounding industrial towns on the 15th and 16th of June 1970 in the following manner:

“Exactly 50 years ago, Turkey was shaken by a workers’ insurgency that still stands as the apogee of working class militancy in the country’s history. The workers of Istanbul and the neighbouring cities of Gebze and Izmit occupied the streets and squares, filling the hearts of the bourgeois with fear, overrunning every barricade set up by the police and the army, forcibly wresting their fellow workers taken under custody from police precincts, chanting slogans on one of the main avenues of the city that has always been the pride of the wealthy so that, in the words of a worker in their ranks, “the rich shall see our power”, and displaying their undeniable power by demonstrating in front of government buildings and local army headquarters. The image of civilians on top of tanks on the night of 15 July 2016 fighting the failed coup made a great impression on international audiences. And yet close to half a century before that the working class had done the same things on the streets of Istanbul! For two days the bourgeoisie and its hangers on shut themselves up in bunkers and Istanbul was conquered by those that made it live through their labour.”

“Istanbul was conquered”. This what we said. Yet little did we know at that time that in a month’s time we would be face to face with a situation where, on the basis of the historical conquest of Istanbul, relying on the legal provisions of the Sultanate, the Council of State would annul the decree passed by the government in 1934 and make it legally binding on the current president to turn the Hagia Sophia into a mosque.

The 1970 events of June were the first time the working class of Turkey rose onto the stage of history as an independent agency. Since then there have been ups and downs in the class struggle in Turkey and, of course also very importantly, in the world surrounding the country. The military coup of 1980 was a full-scale assault on the power that the working class had acquired in the two-decade ascendancy of class struggle from 1960 to 1980. It was, stripped of all ideological ornaments, an answer to the 15th and 16th June events.

The last relics of the junta gone in 1989, after an interlude of roughly a decade, the AKP rose to power. Since day one it has been waging an interminable attack on the rights and gains of the working class through privatisations, the flexibilisation of the labour market, the blatant primacy given to unions that side with the government politically, and, most importantly, the successive episodes of banning strikes. Yet more and more the working class seems ready to strike back, as was witnessed in the wildcat strike in the metal industry in 2015 and the mobilizations during the collective bargaining process of the metalworkers this past winter.

The spirit of 15th and 16th June will, there is no doubt on this, come back. Having conquered Istanbul for only two days 50 years ago, the workers will this time not stop until taking power. This will not be a conquest of one pre-capitalist empire by another. This will not be the struggle of one bourgeois nation against another. This will be the conquest of a class society from the usurpers of all socio-economic and political power in order to unite on an equal footing all nations in a federation of the world so as to see it wither away as also the social classes wither away and all other kinds of oppression are consciously fought against so that there will be no racial, ethnic, religious, gender domination and subordination left.

As one of the great Turkish communist novelists and scriptwriters of the 20th century, Vedat Türkali, says in a rare poem of his, Süleymaniye is what the working class deserves and the working class is what Süleymaniye deserves.

The Balkan revolution and the world revolution will bring countries together in their effort to educate the young generations of the working class not only in the domain of the fraternisation of nations and religions but also in the arts and music and literature. It is then that the grandsons and granddaughters of the workers of Turkey, Turkish and Kurdish, and of Greece, Rum and Yunan, will get together in Istanbul/Constantinople to enjoy the beauty of the Hagia Sophia, which is neither a cathedral nor a mosque but beauty incarnated.

After the final conquest, Hagia Sophia and Süleymaniye will extend arms to each other and summon the Aydohya Temple and the Babri Mosque to embrace in bliss forever.

[1]“Class, State and Religion in Turkey”, in Neşecan Balkan, Erol Balkan and Ahmet Öncü, The Neoliberal Landscape and the Rise of Islamist Capital in Turkey, New York: Bergahn Books, 2017.