Black History Month (BHM) arrives this year under quite exceptional conditions. The last year and a half has witnessed the parallel rise of the largest mass movement the United States has witnessed in decades and the fascist reaction. Immediately following the George Floyd popular revolt that swept across the country, fascist thugs flexed their muscles on a national scale for the first time on January 6th, 2021 with a putsch in Washington, DC. The old-school Democratic Party liberals captured power by riding on the exhaustion and frustration of the masses and the momentary disorientation in the Republican ranks following the January 6th debacle. Their moment of victory, however, lasted short, as they soon found out that they had no idea on how to handle the multi-layered social crisis in their hands[1].

A disgruntled mass movement and Left, a paralyzed center, and a Right momentarily thrown off its track… No wonder February of 2021 passed in relative silence. A full year has elapsed since, and there is still no end in sight to the multi-layered crisis.

What does it mean to celebrate the Black History Month in this context?

For most liberals, Black History Month (henceforth BHM) is a month of silent prayer to domesticated icons of some “respectable” Black leaders and celebration of a few Black capitalists’ “achievements”. They praise the gradualist, “level-headed”, “realistic” achievements of the more reformist sections of the Black liberation movement while raising their eyebrows condemning the “extremism” of the more militant sections, if they do not conveniently forget the latter altogether. Thus, the centuries-long struggle for Black liberation emerges in this view as a single, linear story of respectful Black protest and blessed White benevolence. If this single line of progress goes off track sometimes, it is only because of a handful of “extremists” such as Malcolm X. No wonder, then, that the holders of this line were buried in utter silence in the last BHM!

For the radical Left, on the other hand, it is the militant self-activity of the Black masses expressed through single mass actions (such as the Watts Revolt) or radical leadership that drives the struggle forward. In other words, it is precisely those elements that the liberal narrative deems “extremist” or disruptive that make the quest for liberation possible. Rightfully reclaiming the radical figures of the Black liberation struggle as its own, however, the radical Left can get carried away with the understandable impulse of countering the liberal and right-wing vilification, and thus miss its chance to draw important lessons from the mistakes of the leaders and movements of the past.

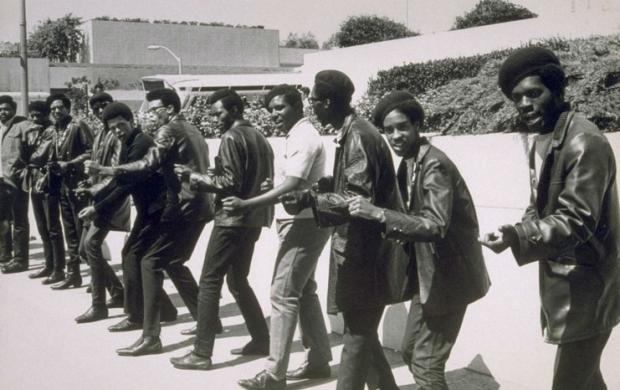

It is precisely this critical appraisal that we seek to accomplish in what follows. To honor the Black liberation struggle and carry it on in the most strategic way, we want to understand one of the most complex and thorny chapters of Black history: the one that was written by the Black Panther Party (henceforth BPP). Marxists never look at history for the sake of purely academic learning. We venture into history to find inspiration to energize our actions today and learn from our precursors’ mistakes. With their vast organization that spanned across the country, their courage in the face of repression, their revolutionary philosophy, and their tragic decline, the Panthers provide abundant lessons to be learned.

We believe that this approach does not contradict our wish to celebrate the BHM at all. For the best way we can honor those who came before us and fought for a better world is to try to actualize their dreams and goals. And to do that requires understanding their strengths as well as weaknesses.

In what follows, we will attempt to assess the BPP’s achievements and failures in that order, and then draw a few parallels between their heyday and our own time. Our aim is neither to write an exhaustive account of the Party’s entire history, nor to unconditionally praise or criticize them. Rather, we seek to draw a balance sheet of the BPP’s strategic, ideological, and organizational orientations to draw lessons for our day.

Origins, or, the BPP as the representative of the Black “underclass”

The BPP was a genuine expression of the black lumpenproletariat and the semi-proletariat that took on an increasingly national-revolutionary character at the time. As the Party grew, it drew Blacks from the proletariat proper and the petite-bourgeoisie into its ranks as well. Nonetheless, the Black urban poor remained by and large its core constituency, as well as their programmatic goal to organize into the foremost revolutionary subject.

As the Panthers themselves often pointed out, Marx and Engels deemed these heterogeneous and erratic social layers untrustworthy and potentially counter-revolutionary. Consisting of chronically unemployed, criminal, and the most wretched social layers, the lumpenproletariat and its neighbor, the semi-proletarian urban poor can be easily bought off by opportunist bourgeois politicians. This class often performed the duty of shock troops and lynch mobs of reactionary politicians, from Louis Bonaparte to Mussolini.

How, then, could such a class organize itself in a revolutionary apparatus, let alone constitute the backbone of a radical movement?

The wage-workers under capitalism constitute the ultimate revolutionary class that possesses a power that stems from its strategic position within the relations of production. However, this does not mean that other social classes or strata cannot ever play a progressive or revolutionary role against the domination of capital. Marx himself vehemently chastised his own disciples who argued that “all other classes are only one reactionary mass” in The Critique of the Gotha Program. While the resistance or revolt of non-proletarian classes is limited or sometimes even reactionary, specific social situations – e.g. a revolt against colonial or imperialist oppression - can assign them key roles in the world-wide movement against capital. As Lenin pointed out in relation to peasant and petite-bourgeois classes of the colonial and semi-colonial countries, while these elements cannot bring about the end of capitalism by themselves, their revolutionary action against imperialist domination lends the revolutionary proletariat an essential support in its struggle with the imperialist bourgeoisie. “There is no ‘pure’ proletarian revolution”, as Lenin liked to emphasize.

The proletarian leadership, in its turn, must carefully listen to these social layers’ grievances, make them of its own, and inscribe them in its program as transitional measures. That is the only way to secure proletarian hegemony in the overall struggle against capitalism, will all evils it causes (including imperialism and racism). To understand what this strategy looks like in practice, we would like to refer the reader to the Communist International’s discussions on the colonial question, and especially to the Congress of the Peoples of The East in Baku, 1920[2].

The Black urban lumpenproletariat constituted just such special social layer in the post-World War II USA. Driven to the big, industrial cities from the South by both racist terror and the promise of industrial jobs in the inter-war era, poor blacks showed remarkable labor militancy and anti-racist resistance during the Great Depression. World War II seemed to promise two things to this recently uprooted, oppressed population: national glory and recognition through a fight against Nazi racism, and rather well-paying jobs to support the war economy[3].

As long as the war continued, these two promises seemed to be working[4]. Among other big cities, Oakland, where the BPP was to be born in the next two decades, was turning into an “industrial garden” with plenty of work in the port, factories, and the railway, and a vibrant working-class black community.

The end of the war meant disillusionment, however. As the war industries and businesses downsized or disappeared, the Black workers were the first one to be fired. The GI bill promised cheap and decent housing to the veterans, but the Black veterans were excluded. The returning Black soldiers faced the same Jim Crow terror in the South, and only a slightly amended version of the same discrimination in the cities of the North and the West. With the introduction of automobiles and suburban housing, capital deserted urban centers for low-tax outskirts. The introduction of new transit technologies seriously downsized, and in case of Oakland completely destroyed, some of the most reliable transport jobs, exacerbating the relative “lumpenization” of the Black working class. The combine effect of all these factors was a desperate, by-and-large unemployed and marginally employed, disillusioned black urban underclass concentrated in the centers, facing police terror and racist discrimination every day. Some members of this class (including Bobby Seale himself) tried their chances to join the military to benefit from the GI bill and respectful recognition only to face the same illusion their WWII-vet forebears did.

At the same time, both domestic and international freedom movements ongoing throughout the 1950s and 1960s, from the Civil Rights Movement to Third World liberation wars, were exposing and attacking the racist and imperialist system underpinning American capitalism. This wide variety of freedom movements with varying degrees of radicalism and often conflicting programs facilitated the spread of ideas of liberation and revolution among the black underclass. Impatient with the incremental progress the Civil Rights Movement was making outside the South, and having caught the revolutionary fervor of the times, the urban black poor expressed their frustration with spontaneous outbursts. For this “ghetto” population, the demise of legal segregation in the South meant little in terms of material gains, for legal segregation was already banned but actual segregation was perpetrated by real estate speculation in the form of “white capital flight”, employment segregation, as well as racist police methods.

The primary Black Rights organization at the time was the Student Nonviolent Coordination Committee (SNCC). Under the pressure of the tensions building in the North and the West and the exhaustion of the legalistic battle in the South that ended the Jim Crow segregation system, the SNCC began its first skirmishes outside the South just around this time, under a new and more militant leadership by Stokely Carmichael. By 1967, Carmichael virtually changed the agenda of the Black liberation struggle overnight by uttering the phrase “Black Power”. “One of the tragedies of our struggle against racism”, said Carmichael, “is that up to now there has been no national organization which could speak to the growing militancy of the young black people in the urban ghetto”. For those false allies that had supported the struggle until “it turned violent”, Carmichael was not sparing his blows: “For once, black people are going to use the words they want to use – not just the words whites want to hear.”[5] The Black masses in urban ghettos were fed up, and were looking for new methods – and new leadership.

This mass off people burst on the scene of American history in 1965 with the Watts Revolt in Los Angeles. In a largely spontaneous outburst against white police brutality, this almost exclusively black neighborhood rose against the powers that be, defying not only the white police terror but also the Civil Rights legend Martin Luther King, Jr., who was immediately flown to Los Angeles with the express purpose of calming down the revolt. MLK was ridiculed, and his follower Dick Gregory was shot in the leg by an anonymous participant of the revolt. Though severely repressed within a few days, the Watts Revolt marked a turning point in the development of the Black Liberation struggle. The ruling class fear of Watts can be inferred from the following flyer that was handed out by Economic Development Administration in Oakland a few months after the event[6]:

LET’S TALK ABOUT PROBLEMS

Eugene R. Foley,

U.S. Department of Commerce,

President Johnson’s Troubleshooter,

Wants to talk to you to prevent a Watts

in Oakland.

If only the knuckle-head who wrote the flyer knew that a much worse storm was coming his way!

It is precisely this energy that the Black Panthers tapped into from their earliest inception. The BPP was the most conscious, most advanced expression of this sentiment of anger and disillusionment of the black underclass. They carried both the revolutionary energy and the strategic limits of the class they came from in an amplified form.

The first Panther cadre by and large came precisely from this social layer of urban ghetto Blacks born in the South and migrated to California as children. Most of these men were placed in a layer between the proletariat proper and the lumpenproletariat. The boundary between the two classes in the postwar black Oakland was exceptionally fine and porous. Seale was dishonorably discharged from the military, and Newton had served his time in prison, including solitary confinement, before the founding of the Party. Seale was working at a welfare office while trying his chance on stand-up comedy scenes, and Newton was an irregular student in the Merritt College. Later, the founder of the first Panther chapter outside of the Bay Area in Los Angeles was a renowned and feared gang leader Bunchy Carter. Only David Hilliard was working in a unionized job at the docks, but was not allowed to work in the higher skilled jobs because he lacked a high-school diploma.

These men were also ardent followers of Malcolm X, who, unlike the southerner Dr. King, was speaking directly to the blacks in the urban ghettos of the North and the West. For most black urban residents who were facing discrimination and police violence on a daily basis, Malcolm X’s rejection of the non-violence dogma of the Civil Rights Movement was a statement of the self-evident truth. However, his persistence linking of the anti-racist fight at home with anti-imperialism abroad proved both novel and powerful for his audience, who included virtually all to-be Panthers. Newton and Seale were both outraged by the assassination of Malcolm X in 1965 as well as the passivity of the Black organizations around them. Bobby Seale was so full of rage that he picked up bricks and threw them at the passing-by cars with white drivers.

Meanwhile, the streets of Oakland were under constant threat of police terror, demolition and physical deterioration. The International Longshore and Warehouse Union (ILWU), itself founded in the wake of the Communist-led 1934 San Francisco General Strike, was the only hope for many Blacks for formal employment with union-level wages. Racial segmentation of the labor market, racist residential zoning laws, and the particularly notorious Oakland police had cornered the Black community into a life of abject poverty and constant fear. The BPP chose to confront this power structure head-on, beginning with its representatives that the Black population was most bitterly familiar with – the police. The iron kernel of the state is specialized armed men, says Engels. The Panthers were to take on this very kernel. “As the aggression of the racist American government escalates in Vietnam, the police agencies of America escalate the repression of Black people throughout the ghettos of America” wrote Huey Newton. “The Black Panther Party for Self-Defense believes that the time has come for Black people to arm themselves against this terror before it is too late.”[7]

Thus began the initial patrolling of the police by the Panthers, using not only guns but also a strategy of exhausting all legalistic methods. Confrontations with the police could be won only by showing the greatest discipline as well as dedication. “At this time the black masses are handling the resistance incorrectly”, Huey Newton reflected later. “The brothers in East Oakland learned from Watts […] This method of resistance is sporadic, short-lived, and costly in violence against the people.[8]” Correct, disciplined methods had to be shown by example. “This [was] the primary job of the vanguard party.[9]” Even the most intense moments of confrontation were to be handled within strictly legal boundaries as much as possible and with strategic finesse. Huey Newton himself exemplified this approach against a police officer who threatened to arrest him as the Panthers were standing guard to Malcolm X’s widow Betty Shabazz. As an over-zealous reporter tried to photograph Shabazz against her consent, Newton pushed him aside, with his gun in his hand. As a police officer threatened him with arrest, Newton calmly loaded his gun without pointing it to anyone, and explained the officer that he had no legal grounds to arrest him. The officer was forced to back off.

The origin story thus far contains two valuable lessons for the American Marxists and revolutionaries. First, in certain material and political conjunctures, individuals or even whole class sections that have not been on the ranks of the more regular revolutionary forces can be politicized into a revolutionary direction. While the historically reactionary role the lumpenproletariat has played in several social crises from the 1848 revolutions to the fifteen long years of crisis in Weimar Germany are undeniable, the African-American equivalent of this very same class in the postwar years was able to produce a revolutionary and daring organization. This fact is enough of a proof to dispel the ouvrierist (workerist) prejudices prevalent in some sections of the American Left. The central role of the proletariat as the single social class able to overthrow the yoke of the bourgeoisie and thereby liberate humanity is unquestionably clear to anyone who is able to understand how our capitalist society works. But the allies of the proletariat at the critical conjunctures are not set in stone, and they have to be sought out through a concrete analysis of the concrete situation at any given moment. As the BPP demonstrates, these allies might even prove to run ahead of the proletariat at times. Malcolm X had been organizing for about a decade when he was murdered in 1965. The BPP took up arms the following years. It was going to take about half a decade for the most advanced, unionized sections of the proletariat to demonstrate nation-wide recalcitrance.

Second, the revolutionary party must show extreme finesse when handling violence. With fascism back on the rise, increasingly larger sections of the working class and other oppressed sections of the society will face fascist street gangs as well as the more ordinary repressive forces (the police, the National Guard, etc.). Revolutionary violence will therefore become a necessity even for purely defensive purposes. Shying away from such violence will become out of question for any revolutionary who takes themselves somewhat seriously. In this field, the Panthers provide abundant examples as to how to mete out violence in self-defense. Arbitrary, unorganized violence provokes stronger backlash and defeats its own purpose. Ranks must be strongly attached to one another, every member must know their responsibilities and possible consequences, and every legal means must be observed and exhausted pedantically.

Speaking of insurrection, “the forces opposed to you have all the advantages of organization, discipline and habitual authority”, Engels says; “unless you bring strong odds against them you are defeated and ruined”[10]. We do not know if the founders of the BPP had these lines in mind when they began training themselves and their cadres both militarily and legally, but they definitely exemplified this approach if anyone has in the US – at least in their initial stages. We have seen what the lack of this approach causes in a many debacle during the 2020 George Floyd Popular Revolt, from Seattle to Kenosha.

But if armed self-defense distinguished the BPP from other Black Liberation groups, it did not and could not guarantee authority to the Party over the Black underclass. It was a time of great ferment in the Black Liberation movement’s history. While the SNCC had set the question of “Black Power” for the movement’s agenda, it was on its own unable to provide the definite answer. In the wake of the victory over Jim Crow, the BPP was far from being the only group that was contending for the position of the Black Vanguard – in fact, it was not even the only Black Panther Party at the time. But it did have something that other groups did not have – an encompassing program arrived at through a comprehensive materialist analysis. And this element was to prove the Panthers peerless in providing leadership for the Black masses – until a certain point.

A materialist analysis, a class-based strategy, and a national-revolutionary program

The BPP was very self-conscious of its material and class basis, and sought to express the interests of the Black lumpenproletariat in a coherent program. In doing so, it also sought to avoid the pitfalls of exclusionary Black chauvinism and cross-class, loose alliances based solely on race.

The 1960s was a high time for “cultural nationalism”, that is, the ideology that the racial and/or national oppression stemmed from a deficient, alienating culture on part of the whites. The solution the upholders of this type of ideology sought was to resign themselves into seclusion from the “white culture”, and search for cultural/spiritual empowerment in a glorified regional past. Frantz Fanon, whose writings had become the banner for Third World Liberation virtually in every corner of the world by the end of the 1960s, had identified this impulse to seek salvation in a past that never was with the Third World bourgeoisie’s economic and political impotence vis-à-vis its former colonial oppressors:

The 1960s was a high time for “cultural nationalism”, that is, the ideology that the racial and/or national oppression stemmed from a deficient, alienating culture on part of the whites. The solution the upholders of this type of ideology sought was to resign themselves into seclusion from the “white culture”, and search for cultural/spiritual empowerment in a glorified regional past. Frantz Fanon, whose writings had become the banner for Third World Liberation virtually in every corner of the world by the end of the 1960s, had identified this impulse to seek salvation in a past that never was with the Third World bourgeoisie’s economic and political impotence vis-à-vis its former colonial oppressors:

After independence, the [bourgeois] party sinks into an extraordinary lethargy … [T]he national bourgeoisie of underdeveloped countries is incapable of carrying out any mission whatever. After a few years, the break-up of the party becomes obvious… The party is becoming a means of private enrichment.[11]

Once the bourgeoisie begins to splinter into factions, the ruling faction begins to rekindle tribal, ethnic, religious frictions that existed before independence, and disseminates these through the works of the “native intellectuals”:

[The intellectual] sets a high value on customs, traditions, and the appearances of his people; but his inevitable, painful experience only seems to be a banal search for exoticism. The sari becomes sacred, and the shoes that come from Paris or Italy are left off in favor of pampooties … [12]

This type of nationalism made its way into the United States as well. The flashiest of its upholders, arguably, was the members of the US[13] Organization, who shaved their heads, wore pseudo-African dashikis, changed their names into Swahili, and sought to cleanse their souls in “Soul Sessions”. Their demand for cultural autonomy for African-American and exploration of the African culture as a counter-reserve against the alienated and alienating culture of American imperialism were indeed constituted an important step forward in the Black Liberation struggle’s unfolding. However, this solely culturalist ideology could find no solution to the material plight of the Black masses, whether in the post-Jim Crow South or in the Northern or Western ghettos. The founder and chief ideologue of the US Organization, Ron Karenga, justified their position with the following words:

Cultural background transcends education … Membership in the Black community requires more than physical presence. In terms of history, all we need at this point is heroic images … US is a cultural organization dedicated to the creation, recreation, and circulation of Afro-American culture … We must free ourselves culturally before we succeed politically.[14]

The Black Panthers’ brand of nationalism stood in stark contrast to this type of Black culture advocacy. From their inception onwards, the BPP made it their core strategy to engage in the community’s most urgent material struggles. The analysis of the material conditions in which the Black masses found themselves in was the beginning, the betterment of these abject conditions was the end goal. Thus, the Panthers sought a double strategy with each component supporting the other: armed self-defense and engagement with the material conditions of the Black ghetto. Newton and Seale summed up their vision at the very inception of the Party in the famous 10-Point Program, of which we shall speak more below.

From Huey P. Newton and Bobby Seale’s initial drafting of the 10-Point Program onwards, this method of engaging with the community became the single guiding thread of the Party’s strategy. In fact, Newton was even willing to give up armed and uniformed parades and gun-centered slogans – the very symbols that made the Party popular in the first place - if they jeopardized the relationship between the Party and the Black community. Huey Newton himself summarized the BPP’s distinction between their own brand of “revolutionary nationalism” and “cultural nationalism” in his famous prison interview in 1968:

There are two kinds of nationalism, revolutionary nationalism and reactionary nationalism. Revolutionary nationalism is first dependent upon a people’s revolution with the end goal being the people in power. Therefore to be a revolutionary nationalist you would by necessity have to be a socialist. (…) Cultural nationalism, or pork chop nationalism, as I sometimes call it, is basically a problem of having the wrong political perspective. It seems to be a reaction instead of responding to political oppression. The cultural nationalists are concerned with returning to the old African culture and thereby regaining their identity and freedom. In other words, they feel that the African culture will automatically bring political freedom. Many times cultural nationalists fall into line as reactionary nationalists.[15]

This materialist analysis led the BPP to a class analysis. Unlike the progressive Black organizations of previous decades, the Panthers did not believe that individual, successful black capitalists’ generosity would save the Black community from their plight. Instead, the poor blacks, the lowest of the low in the American social hierarchy, were to organize themselves into a revolutionary vanguard to overturn the entire system. And if the entire system was to be overturned, the poor blacks needed allies who had a stake in such a great revolution. In the US context, this meant organizing with other people of colors’ liberation organizations, as well as the poor and progressive whites. The racist hierarchy was not going to be simply reversed, as some cultural nationalist organizations claimed, it was to be completely abolished. Moreover, abolishing race as a social division and hierarchy was directly linked to abolishing capitalism: “We are for all those who are for the promotion of the interests of the black have-nots”[16].

This class-based analysis and policy of selective alliances, as we shall expand upon later, drew reaction not only from the BPP’s competitors for leadership but also from some of its erstwhile allies. After aligning himself with the BPP for a short period, the legendary former leader of the SNCC denounced the Party precisely on the grounds of its alliance with white radicals and progressives. Committed to the liberation struggle of all oppressed peoples not only within the US but globally, the BPP’s response to this Black sectarianism was rapid and harsh. “We are a Marxist-Leninist party, and implicit in Marxism-Leninism is proletarian internationalism, and solidarity with all people who are struggling and this, of course, includes white people”, said Eldridge Cleaver, the Minister of Information of the BPP at the time, a little before he himself began his disgraceful political descent. Not having any policy towards whites, he added, the BPP considered “to be racist”. [17] Huey Newton also denounced Carmichael in 1970 with aligning himself with US imperialism by stating that the new post-colonial “governments are saying that if the United States will let us exist as a class to oppress our African people then we will cooperate; in other words, Black oppressing Black. This is Stokely Carmichael’s philosophy”[18]. Newton took it so far as to charge Carmichael for being an accomplice of the CIA, though without offering much support to the charge.

If the initial police patrols in the streets of Oakland announced the Party’s arrival on the political scene loud and clear, their independent investigation into the murder of Denzel Dowell - a young black man who had been shot by the police in the nearby town Richmond in 1967– and their publicization of the event in the very first issue of their paper Black Panther posed them to the poor Blacks of the Bay Area as a real alternative leadership. The BPP’s willingness to engage in the minutest details of the case, as much as their audacity and discipline, completely charmed the residents of the Black ghetto in Richmond. Unlike the local authorities and rather timid organizations of the limited Black bourgeoisie that the people of Richmond found to be in a joint conspiracy of silence, the Panthers took up the case, organized rallies that blocked important highway intersections, and preached self-defense. Dowell’s brother George later recalled: “I was really impressed. They made me feel like they were really interested in the people, and they knew what they were doing.”[19] As the Party grew exponentially in the following years, their community service activities also began reaching broader and deeper, creating almost “dual power” situations in a many urban ghetto (we shall talk about these activities later).

These two visions of Black nationalism – one based on materialist analysis, the other on cultural terms – were bound to clash sooner or later[20]. Especially in the context of the late 1960s, where urban revolts, anti-war movement, and the government attempts to contain them were all in full-swing, competition for leadership over Black masses became particularly intense. Inevitably, the Black Panthers and the US members confronted each other in less than pleasant situations. Heavily infiltrated by the FBI, the US Organization was in a perfect position to let itself be used by the very oppressor it was fighting against. At the highest point of contention, and despite the BPP leadership’s imposition of restraint on its members against other Black organizations, the US militants ended up killing two Los Angeles Panther leaders Bunchy Carter and John Huggins[21]. While the entire surviving leading cadre of the Los Angeles BPP were rounded up and arrested in their houses, and the Party office in the city was sieged by SWAT teams, only two members of the US Organization were arrested for murder. The two individuals who were witnessed by various people to have engaged in the shooting vanished altogether. Cultural nationalism had, indeed, fallen in line with reactionary nationalism, as Huey Newton had predicted.

Cultural nationalism is still very much alive today, although it has dropped its radical garb entirely. Especially on campuses, the term “decolonization” has become some sort of a fashion. From faculty unions to student baking clubs, every campus milieu with some level of left leaning seeks to “decolonize” their institution, “un-think”, “un-learn” or “re-imagine” their lives, and break from “colonial legacies” of everything (from thinking to cooking). While this awareness of the imperialist legacies in culture and institution is worth congratulating, it is rather evasive when it comes to challenging the material foundations of these divisions. More often than not, this type of politics culminates into celebrating some businessperson of color’s achievements and militating for some sentimental-talking Democrat. Neither figure has any problem oppressing and exploiting the working class, colored and white alike. Moreover, accusing everything on the “white/colonial culture” alienates the poor whites, pushing them into the arms of fascist politicians like Trump.

The Left has a lot to learn from the materialist, class-based analysis of the Panthers and their revolutionary politics that was geared towards winning as many poor people across the color line to fight against “the Man”. Addressing the real, material issues of the community and attempting to bridge the gap across the racial division lines was and is an immense undertaking, and the BPP had both great accomplishments and grave errors (as we shall see below). However, the fact that they chose to fight against racism by challenging its material basis and by uniting the poor across the color line on equal footing speaks volumes.

Engagement with the poor Black communities distinguished the Party not only from the cultural nationalists but also other armed Black Liberation organizations as well as their white equivalents. Most of these groups, not a few of which were also named “the Black Panthers”, would emphasize the need for patrolling the police or even armed confrontation, but had no way of effectively implementing that strategy. Without having cast their roots deep in the communities they sought to represent and defend, these groups remained isolated and vulnerable to quick police repression or intimidation by other groups (including the BPP). Therefore, while these groups burst on the scene and quickly vanished between 1966 and 1969, it took a full decade (1970-1980) for the BPP to completely unravel, despite bearing much heavier repression than any other group.

The BPP did not shy away from criticizing its white imitators either. Following the 1968 Chicago Revolt against the Democratic Party convention, in the city, the white “radical” Weathermen organization unnecessarily escalated conflicts with the police without a mass to back them up in Chicago. The chairman of the local BPP Fred Hampton did not spare his blows: “They are doing exactly what the pigs want them to do. They’re leading people into a situation [inaudible] astronomical situation, too big of a situation for people to deal with … and they’re talking about they are going to carry on the revolution. That’s not revolution, that’s insanity[22]”.

It was thanks to this double strategy of courageous and disciplined confrontation with the repressive forces and direct engagement with the Black underclass to better its conditions of living that allowed the BPP to enjoy an authority no other Black Liberation organization enjoyed. Even the SNCC, the ideological forebear of the BPP if there ever was one, had difficulty adapting itself to the conditions of the Northern and Western ghettos. Shattered with programmatic differences, the SNCC ended up splitting, with one section dissolving itself into the BPP and the other vanishing.

Unlike most groups that sprang up in the same era, the BPP was very careful to express its strategy and goals in its famous clearly worded, precise and succinct 10-Point Program. Newton and Seale paid special attention to its simplicity and familiarity of its language to the “brothers [sic] on the block” as much as its broad content. The result was, in Hilliard’s words, a manifesto that “read like a bill of rights, with its political and economic agenda, partly constitutional, and partly inspired by the Declaration of Independence”[23]. In fact, the Program and the Party were justified by a lengthy citation from the Declaration of Independence, with an emphasis on the section on the right of secession, thereby pointing to continuity within the American revolutionary tradition.

The content of the program was based on the most burning needs of the Black community in Oakland at the time, but it proved to be generally applicable to the conditions of virtually all Black ghettos around the country: freedom, employment, housing, an end to police brutality, trial by peer groups for black prisoners… This clear expression of the most pressing needs of the poor Black community, along with the Party’s undying commitment to global anti-imperialist revolutionary politics, was to prove the program’s greatest merit.

The 10-Point Program can hardly be called “socialist” – there is no mention of the need for the expropriation of the bourgeoisie, socialization, etc. Control over the means of production and land are mentioned only as threats: “if the white American businessmen will not give full employment, then the means of production should be taken from the businessmen…”. Similarly, “if the white landlords will not give decent housing to our black community, then the housing and the land should be made into cooperatives…[24]” As such, these mainly economic demands have the merit of acting as transitional demands for more revolutionary demands, leading up to the expropriation of the bourgeoisie as such. Yet, the initial Panther program does not contain any measures that can be called “socialist” in its economic content, though it does contain points of departure into that direction. The transitional nature of these demands was proven in 1969, when the BPP changed the wording of the third point from “we want an end to the robbery by the white man of our Black communities” to “an end to the robbery by the CAPITALIST”, thus taking on a more explicit and concrete class content.[25]

Demands of a more political nature, such as exemption from military service and freedom for all black men in jail, are more audacious, in that they explicitly lay out the strategy of armed self-defense and link the Party’s struggle with that of the Vietnamese people against American imperialism. This link runs like a red thread throughout the Party’s entire existence.

The greatest danger in the program is the parallel it sets between the rightful demand of Black Liberation struggle for reparations to the German aid of the Zionist State of Israel in the Middle East in Point 3. While opposing colonialism and imperialism at home and abroad, the Panthers thus were undercutting their own platform by linking their own rightful demand of reparations to the aid by one imperialist country (Germany) to a settler-colonialist entity (Israel). While the Program was subject to revision over the course of the next few years, these sentences were never dashed out, even after the BPP declared solidarity with the Palestinian struggle or Huey Newton himself got into contact with the PLO leaders. The Party showed an unflinching pro-Palestinian attitude in the late 1960s and early 1970s, despite the criticisms of its white allies. In 1974, however, the BPP was to declare that it recognized the State of Israel, demanding only that Israel gave back the territories it had invaded after 1967.[26]

Thus the program has a hybrid status, based on the most urgent minimum demands of the poor Blacks, with some economic advances that can be called transitional. This puts the BPP neatly into the Leninist category of a “national-revolutionary” organization, that is, a “genuinely revolutionary” organization that does not hinder communist development or organizing, but does not have a proletarian-revolutionary (aka communist) program due to its class nature[27]. Of course, this term has to be stretched a bit to be adapted into the post-war US conditions, because the class in question is not “peasants who represent bourgeois-capitalist relationships”, which Lenin spoke of[28], but a lumpenproletariat and a semi-proletariat that were underdeveloped precisely by the very dynamics of the most developed capitalism in the world. Nonetheless, the same marginality yet vital function within imperialist capitalism and the national/racial oppression arising out of this dialectic is common to both cases, as the BPP itself was aware of.

Thus, the BPP possessed in its arsenal both a clear strategy and a succinct national-revolutionary program – two elements that were necessary for it to enjoy the leadership status that it did. However, without an exemplary discipline, versatility in its tactics, and principled alliances, even the best program is doomed to vanish in the air. The Panthers were a master of all these elements, which we shall speak in our next section.

[1]For our assessment of the process, see James Cooper, “One year after the fascist putsch: farce is turning into tragedy”, http://redmed.org/article/one-year-after-fascist-putsch-farce-turning-tragedy

[2]For an appraisal of the Baku Congress and its relevance today, see https://gercekgazetesi.net/english/new-baku-congress-peoples-east-united-front-workers-and-toilers-mena-and-caucasus

[3]Joshua Bloom and Waldo E. Martin, Jr., Black Against Empire: the History and Politics of the Black Panther Party, Oakland 2016: University of California Press, p. 27.

[4]The following two paragraphs follow Robert O. Self, American Babylon: Race and the Struggle for Postwar Oakland, Princeton 2003: Princeton University Press, pp. 142 ff.

[5]Stokely Carmichael, “Power and Racism” in The Black Power Revolt, Floyd B. Barbour (ed.), Boston 1968: Extending Horizons Books, p. 61-62.

[6]Cited in Black Against Empire, p. 38.

[7]Huey P. Newton, “In Defense of Self-Defense: Executive Mandate Number One”, in Philip S. Foner (ed.), The Black Panthers Speak, Chicago 2017: Haymarket Books, p. 40.

[8]“The Correct Handling of a Revolution”, The Black Panthers Speak, p. 41.

[9]Ibid.

[10]Friedrich Engels, The German Revolutions: The Peasant War in Germany and Germany: Revolution and Counter-Revolution, Chicago and London 1967: University of Chicago Press, p. 227.

[11]Frantz Fanon, The Wretched of the Earth, New York 1968: Grove Press, p. 171.

[12]Ibid., p. 220.

[13]Pronounced as in “us versus them”, and not as in the abbreviation of the United States.

[14]Maulana Ron Karenga, “from the Quotable Karenga” in The Black Power Revolt, pp. 162-164.

[15]“Huey Newton talks to the Movement About the Black Panther Party, Cultural Nationalism, SNCC, Liberals and White Revolutionaries” in The Black Panthers Speak, p. 50.

[16]Same interview, p. 51

[17]Eldridge Cleaver, “Eldridge Cleaver Discusses Revolution: An Interview from Exile” in The Black Panthers Speak, p. 110.

[18]“On the Middle East” in To Die For the People, San Francisco 2009: City Lights Books, p. 195.

[19]Quoted in Black Against Empire, p. 53.

[20]The following paragraph is based on the personal account of Elaine Brown in A Taste of Power: A Black Woman’s Story, New York 1992: Anchor Books, pp. 164-170.

[21]Elaine Brown, an LA Panther at the time and the to-be Chairman of the Party after Newton’s exile, was among the arrested. A talented musician, she composed a beautiful ballad to honor her fallen comrades Bunchy Carter and John Huggins. See: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MAho3vRgSPU

[22]For the full interview, see: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ft3wOPEd28k

[23]David Hilliard, Keith Zimmerman, ad Kent Zimmerman, Huey: Spirit of the Panther, New York 2008: Basic Books, p. 28.

[24]Cited from Points 2 and 4 in the 10-Point Program, our emphasis.

[25]See Black Against Empire, p. 300. Emphasis in the original.

[26]Greg Thomas, “The Black Panther Party on Palestine”, https://www.hamptonthink.org/read/the-black-panther-party-on-palestine. Brown also recounts that Huey Newton had a personal reason relating to his Jewish paternal grandfather in taking this position. According to Brown, this sudden decision threw the Party ranks into disarray and shook the alliance with the PLO. See A Taste of Power, p. 254-255.

[27]V. I. Lenin, “Report of the Commission on the National and Colonial Questions on the Second Congress of the Communist International”, in The National Liberation Movement in the East, 1969 Moscow: Progress Publishers, p. 284.

[28]Ibid., p. 283.