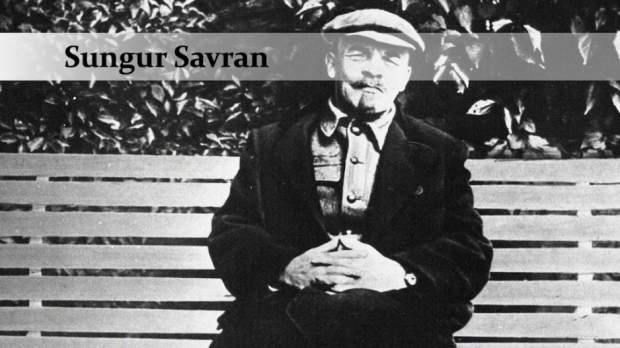

21 January 2024 is the centenary of the death of Vladimir Ilich Lenin, one of the greatest leaders of the international working class. At DIP (Revolutionary Workers’ Party, Turkey) and at the International Socialist Centre Christian Rakovsky, this is the Lenin Year for us.

Why? Because Lenin fought all his life for the poor, exploited and oppressed classes and strata of humanity, starting of course with the working class. He is the great leader who led to its triumph the revolution in Russia that started in February 1917 and struggled to expand this triumph to the continents of Europe and Asia. Most importantly, he is a leader of the international proletariat, the bearer of the emancipation of the human race.

Lenin was, among the revolutionaries of the modern age, the one who best observed the old mole meticulously and recognised him as soon as he hit upon him. And who might be this “old mole”, you will probably ask. To understand that, we need to go back to the greatest leader of revolution in the modern age, Karl Marx. Marx uses the figure of the “old mole” in order to point to the long-drawn-out process that prepares revolutions. His sources of inspiration are William Shakespeare, the great poet of the age of bourgeois revolutions, and the philosopher G. F. W. Hegel, the father of the dialectic in early 19th century. The common trait of the figure of the “old mole” in Shakespeare and Hegel is that they both attribute to the old mole the accomplishment of a most onerous task over a long period of time.

Marx himself attributes to the “old mole” the duty of preparing the conditions of revolution. The revolution burrows its way forward for a long time underneath the ground. The soil then thins, threatening the bases of the social order of exploitation. Its collapse becomes a matter of one single blow. Then when that blow comes, the mole emerges into sunlight and it is now the heyday of revolution. Thus, the revolution carries out its onerous duty without us feeling, let alone seeing, this work being completed. In his rightly famous mid-19th century analysis of France during the revolutions of 1848 and the subsequent coup d’Etat of Louis Bonaparte, titled The 18th Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte, Marx explains his jubilation that revolution is now on the agenda by exclaiming, “Well-burrowed, old mole!” The revolution, after years of coming-of-age, is now ready to come out.

That means the revolution refrains from revealing its activity. It runs silent and it runs deep, then it comes out unexpectedly. If this is the case, then what are the symptoms one should be on the lookout for? What developments should one be alert to?

We should first pay attention to Marx’s example. We will then turn to Lenin. When Marx wrote, “Well burrowed, old mole!”, France had only recently come under the tyranny of a dictator who left his mark on European history. Bonapartism, from the name of the dictator Louis Bonaparte, is a concept still used to describe a certain type of regime in political science. In a society where the opposed classes cannot overcome each other, where the balance of forces does not permit the victory of one over the other, a dictator with origins outside of the usual political personnel of the bourgeoisie takes over power to rule in place of the ruling class but in conformity with its interest. Attention! Just as a new dictatorship has been established to serve the interests of the bourgeoisie, Marx contends that revolution is carrying out its preparatory work unseen and unsuspected. Probably at a moment when petty-bourgeois leftists were tearing themselves apart with great disillusionment in revolution, Marx insists that revolution is preparing the ground.

This is not the place to discuss the economic, political, diplomatic etc. conditions of mid-nineteenth century France that made possible this preparatory work for revolution. What we should pay attention in Marx’s method is the following: he claims revolution is at work precisely at a moment when things have turned sour. This is what we should try to understand.

The deeper meaning lies in this: under certain circumstances, the recourse by ruling classes to extraordinarily harsh, despotic, tyrannical methods implies that they are unable to rule as before. If this is true, then it creates an environment in which the revolution can surreptitiously carry out its preparations. It is dialectics that is at work here. A process need not be one-sidedly positive or negative. It is the unity of opposites. The recourse on the part of the bourgeoisie to open dictatorship may mean, under certain circumstances, that revolution has found the conditions in which it can move forward. Conversely, the rise of revolution contains the menace of counter-revolution almost inevitably. The revolutionary party, making use of revolutionary theory, is faced with the task of discovering the type of unity of opposites the proletariat faces at any given moment.

In the case of France, Marx erred on the question of timing. The old mole completed its work much more belatedly when compared to Marx’s expectations. But apart from that, the prediction came true down to each detail. What put an end to the Bonapartist regime was the Paris Commune, the first revolution that brought the working class to power in 1871, albeit only for a short period of 72 days.

“Mittelding zwischen Traum und Komödie”

Now we possess all the elements necessary to fast forward approximately four decades. The time is 1914 and later. The place is not a single country this time, but the whole of Europe. Since Europe rules over the whole world, it in fact the entire world. The scene is the greatest slaughterhouse that humankind has so far ever seen: World War I between 1914 and 1918, which devastated not only Europe but the peoples of the colonies as well.

Marx’s legacy has now been inherited by Lenin, the leader of the Bolshevik Party, a party that is trying to turn the impetuous struggle of the working class of that country into a vortex of revolution. When the war broke out, a great majority of the workers’ parties across Europe became warmongers marching behind the bourgeoisie of their own country. Lenin and his comrades, on the other hand, had already started to wage war against the war in intransigent manner.

The assumption behind the policy line of Lenin concerning the war is that the world is advancing towards a revolutionary situation. This is what Lenin is saying: if the ruling classes cannot rule in the same old way, and more importantly, if those ruled do not wish to be ruled in the same manner as before, and there are certain symptoms that show that the masses will move forward, then there is a revolutionary situation, which does not imply yet that a revolution has broken out. Hence everything must be done to turn the slaughterhouse into a revolution. The working class needs to take power. This is the way to put an end to the war.

This view of the state of the world is diametrically opposed to the so-called working-class leaders who have now passed over to the camp of their ruling classes and are warmongering or, in the best of situations, looking for a bourgeois leadership in order to stop the war. In their view, humanity is light years away from a revolutionary situation. A reactionary atmosphere dominates all countries. Hence the expectation of a revolution is nonsense.

When, in the midst of the war, the February 1917 revolution erupts, when, in other words, the revolutionary situation that Lenin was talking about turns into a revolution in action with a single spark and brings down in the space of five days the mighty Czar, Lenin, having decided to return to revolutionary Russia, writes a “Farewell Letter to the Swiss Workers”, and comments thus on the debate before the revolution:

“When, in November 1914, our Party put forward the slogan: ‘Turn the imperialist war into a civil war’ of the oppressed against the oppressors for the attainment of socialism, the social-patriots met this slogan with hatred and malicious ridicule, and the Social-Democratic ‘Centre’, with incredulous, sceptical, meek and expectant silence. David, the German social-chauvinist and social-imperialist, called it ‘insane’, while Mr. Plekhanov, the representative of Russian (and Anglo-French) social-chauvinism, of socialism in words, imperialism in deeds, called it a ‘farcical dream’ (Mittelding zwischen Traum und Komödie – something between a dream and a comedy). The representatives of the Centre confined themselves to silence or to cheap little jokes about this ‘straight line drawn in empty space’.

Now, after March 1917, only the blind can fail to see that it is a correct slogan. Transformation of the imperialist war into civil war is becoming a fact.

Long live the proletarian revolution that is beginning in Europe!”

How is it that Lenin advanced the idea of a “revolutionary situation” precisely at the moment when a slaughterhouse of human victims had been set up? Did he simply disregard dogmatically all the adverse conditions? No at all! On the contrary, he saw even better than his adversaries the negative aspects of the situation, for it was not only that imperialist capitalism had thrown million of workers and peasants on the battlefields of Europe to massacre each other, but also the fact that so-called socialists had decided to slavishly follow the orders of the bourgeoisie. It was precisely because he saw how disastrous the situation was that he inferred that the world tended towards a “revolutionary situation”.

He thought in dialectical terms. Having recently studied Hegel and his dialectics, he grasped events and development in their contradictory becoming as the unity of opposites. Under certain conditions, the capitalist tendency towards barbarism would be indissociably tied to the tendency towards proletarian revolution. This war, he understood, was the result of the fact that capitalism had exhausted its possibilities, at least momentarily, and proved that “the ruling classes were not able to rule as before”. The many mutinies in the military forces of each country, the powerful workers strike movements, the revolt of oppressed nations from Ireland in Western Europe to Central Asia in Czarist Russia showed to him that neither did the ruled consent any longer to be ruled as before. These were the bases of his diagnostic of a “revolutionary situation”.

The Ukraine war, the Gaza genocide, The Taiwan tinderbox, the seeds of fascism everywhere

Today as well, the world is entering, or has already entered, a similar historical moment. World War III has not broken out yet. Nowhere has fascism managed to establish its rule on the basis of its own ideological-political premisses yet. But for those who do not want to shut their eyes to reality, many signs have already gathered pointing in this direction. The ruling classes cannot any longer rule as before.

Large swathes of labourers in many countries of the world are resorting to strikes and demonstrations, thus raising class struggle. Faced with the catastrophic massacre, genocide indeed, the Palestinian people are being subjected to, working people and youth all around the world are coming out every week in their tens, if not hundreds of thousands. Most importantly, revolutionary eruptions have not ceased to occur since the Tunisian and Egyptian masses first brought down long-time dictators in 2011. World revolution has not yet found the road to power, but it has started early on in the havoc born of the economic depression that has gripped the world since 2008. Those ruled do not consent to being ruled in the same old manner.

The old mole is working like a factory under the soil. Put your ear on the ground and listen: you will hear the growl and the mutter. But do not be misled. We are not saying we will no longer see bad times. What we are saying is that when we are going through those bad times, we should not despair. What we are saying is this: at the end of the road, there will definitely be a confrontation between fascism and revolution, between all kinds of tyranny and revolution, between a slaughterhouse of human victims, a war that will make World Wars I and II look pale in cruelty and violence, on the one hand, and revolution, on the other.

Do not look for refuge anywhere in the world. Mars has already been taken by the enemy and nowhere will be safe on earth itself. Do not withdraw into a melancholy existence. Do not say to yourself “I will care only for my own family”. Do not say to your child “I will keep you away from the dangerous struggle”. If a world war breaks out, no one can avoid it, especially in this nuclear age. That kind of war will swallow everyone’s child. If fascism, not in the sense it has been used and abused for all kinds of repression, but the real stuff of the Nazi type, if genuine fascism descends upon us, no working-class family can remain immune to the catastrophe that will visit us.

The only salvation is preparation for the revolution. The condition for this, in turn, is to organise in a Leninist party and a revolutionary International, a party of world revolution.

This is the message for the Lenin Year.