All men are equal, but those in Madagascar do not know this.

Voltaire

In Indochina, Madagascar, or in the colonies

the native has always known that

he need expect nothing from the other side.

Frantz Fanon

An old friend whose father was an ambassador once told us that black domestic workers who served whites in Africa developed a special protocol that continued to exist even long after the colonial era ended and independent states were established across almost the entire continent, a protocol that would make it possible not to have to say ‘no’ to their white ‘masters.’ Say a white ambassador returns home in the evening and the door is opened by the ‘servant.’ Say the white “master” asks the black servant if his wife has returned home. If the woman has not yet returned, the servant would have to tell the master ‘No, she hasn't returned’ in order to provide accurate information. But the servant is strictly forbidden to say ‘no’ directly to the master! This could be seen as disrespectful, contrary to good manners, or even rebellious. So, what should the servant do? The answer is ‘Yes sir, no master’! Even when he needs to say ‘no,’ the servant must say ‘yes’!

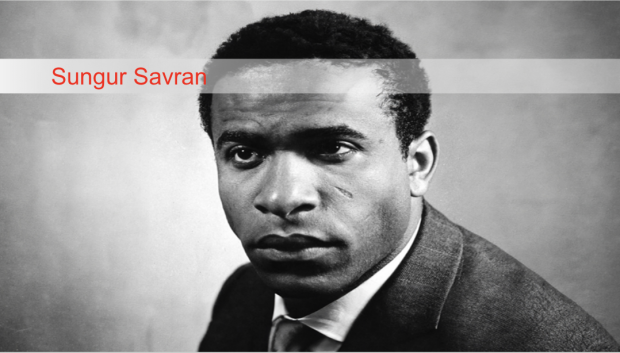

This is the despicable colonial system that placed black people and all colonised peoples, the so-called ‘yellow race,’ the ‘coloured peoples’ from Indonesia to India, the indigenous peoples of America, and the Arabs from the Maghreb to the Mashreq in a subhuman position. One of the sharpest critics of this system, Frantz Fanon, who dealt a great intellectual blow to this system with his book The Wretched of the Earth, written in 1961, is 100 years old today. If Marxism is to liberate the world from the domination of capital and the bourgeoisie, it must carry its victory through to a world revolution. In its struggle for this noble cause, its greatest allies are the national liberation movements and their internationalist leaders, such as Kwame Nkrumah, Patrice Lumumba, Thomas Sankara, César Augusto Sandino, as well as the great theorists and thinkers of the oppressed nations, such as Frantz Fanon, José Martí, Walter Rodney, Steve Biko, Ghassan Kanafani, and countless others.

By commemorating Fanon in this article, perhaps not in sufficient depth, we aim to pass on to young revolutionary Marxists an important link in the chain of liberation struggles of the peoples of Asia, Africa, Latin America, and, of course, the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region.

A Marxist psychiatrist whose ancestors were slaves

Frantz Fanon was born on 20 July 1925 in Martinique, one of the islands known as the Antilles, part of what is still a string of French colonies, but referred to as ‘Overseas Departments and Territory’ (DOM-TOM) and thus considered part of the ‘mother country.’ The son of a father who was a civil servant of the French republic despite his enslaved ancestors, he was raised in quite well-to-do conditions. After World War II, while studying psychiatry in Lyon, an important industrial city in France, he developed an interest in social issues and philosophy, studying the works of Hegel, Marx, and Lenin, among others. He was also deeply influenced by the French philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre, whose fame rose to its apex in the 1950s and 1960s, as he was working to unify Marxism with existentialist philosophy.

In 1952, at the age of 27, Fanon published a series of essays approaching the colonial issue from a Marxist perspective in a book titled Black Skin, White Masks. Here, he describes how black, ‘yellow,’ ‘brown,’ and “native” people in the colonies live in a state of enormous alienation, how Hegel's master-slave dialectic differs in the colonial context, and how, unlike in historical class relations, the ‘native’ is reified, stripped of his humanity, and turned into an object. As one dimension of this relationship, he focuses on the mechanism by which intellectuals, careerists, and those struggling to save themselves individually among the natives became ‘white Negroes’. The native can only become a ‘person’ in the coloniser's world by escaping from being himself. Donning a ‘white mask’ on ‘black skin’ is the method used to achieve this.

After his time in France began Fanon's Algerian period. As a black descendant of slaves, he was appointed as a French psychiatrist to France's most valuable colony. There, in the city of Blida, he spent three years as the head of Algeria's largest psychiatric clinic, where, along with another doctor who was a veteran of the Spanish Civil War, he developed social therapy methods to treat both ‘native’ patients and patients from mainland France. He summarised the main lesson he learned from his experience as a doctor as follows:

“Madness is one of the means man has of losing his freedom. And I can say, on the basis of what I have been able to observe from this vantage, that the degree of alienation among the inhabitants of this country is frightening. If psychiatry is the medical technique that aims to enable man no longer to be a stranger to his environment, I owe it to myself that the [Algerian] Arab lives permanently an alien in his own country, lives in a state of absolute depersonalisation." (Towards the African Revolution).

Fanon, working as a Marxist psychiatrist, did not fail to recognise that, alongside the ‘patient’ he cared for, and perhaps even exclusively, it was the society in which he lived that was ‘sick.’ If people cannot adapt to society, this is by no means solely due to their own personal characteristics; social conditions have a decisive influence.

The militant Marxist psychiatrist of the Algerian revolution

Fanon not only understood that the indigenous peoples of the colonies lived a life of absolute reification and not only did he fight to make this known to the world from a young age, but he also participated personally in the revolution. The issue of foreigners participating in the revolutions of other countries is a very complex historical issue. In the Russian Revolution (e.g., Radek and Rakovsky), in the Latin American Revolution (Che in the Cuban and Bolivian revolutions, many Mexicans in the Nicaraguan revolution, and countless other examples), and in the Turkish revolutions (Balkan revolutionaries in the Freedom Revolution of 1908, Tatars like Yusuf Akçura and other individuals from Turkic peoples in the National Struggle), this, in short, is a characteristic that has been observed in all revolutions. Fanon, who was neither Algerian nor even Arab, but rather the grandson of a ‘black-skinned’ family deported from Africa to the Caribbean region, became one of the leading representatives of the Algerian Revolution, itself a pinnacle of the post-World War II Colonial Revolution, and not content with that, he also became the international representative of this revolution.

The Algerian revolution began in 1954. Even during his time at the hospital in Blida, as the young head of the psychiatry clinic, he played a pivotal role in secretly trafficking all kinds of illegal weapons, bombs, logistical supplies, etc. He created a parallel structure within the hospital to provide every kind of support to the revolution. Furthermore, as a psychiatrist, he shared his professional expertise in psychiatric knowledge with the guerrillas, teaching them how to control their reflexes during bombing operations and how to resist torture. For all these reasons, the French colonial administration expelled him from Algeria in 1956, despite having invited him there in 1953. This move by the enemy served as the catalyst for Fanon's transition to full-time professional revolutionary activity.

Marxist theorist, militant and leader of the African revolution

After his expulsion, Fanon settled in Tunisia, Algeria's eastern neighbour, and devoted all his time (apart from his intellectual work) to organising the Algerian revolution.

He initially served on the editorial board of the revolutionary newspaper El Mujahid, and later became the spokesperson for the Provisional Government of the Algerian Republic (GPRA) at various international conferences.

This was the period when the colonial revolution was in full swing. During these years, many African countries, including the Congo, which the great novelist Joseph Conrad referred to as the ‘Heart of Darkness,’ took steps towards independence. Ghana gained its independence under the pan-Africanist Kwame Nkrumah, and its capital, Accra, became the general headquarters of the African revolution. Fanon settled in Accra for a time as the spokesperson for the Algerian revolution. His path would intersect with that of Patrice Lumumba, the historic hero of the Congo who was assassinated in 1961 while serving as prime minister of the newly independent state, and with that of Moroccan revolutionary leader Ben Barka, who would also be assassinated in a French imperialist plot, as well as with all the other revolutionary leaders across Africa.

In similar fashion with Che Guevara, who would later embody in his slogan ‘Two, three, many Vietnams’ in order to squeeze imperialism from multiple fronts in the 1960s, Fanon insisted on the possibility of launching a revolution in Angola (then under Portuguese colonial rule). He would deepen his relations with the Angolan revolutionary movement (and in the process would make some serious mistakes, but that is not our concern here).

As seen in almost all genuine revolutionaries, Fanon's determined and consistent revolutionary spirit carried him from the anti-colonial revolution to internationalism. We can see the extremely touching result of this in the following example: At the end of 1960, Fanon found out that he had leukaemia and that he had only a few years or even a few months left to live. He was admitted to a hospital in Moscow. The doctors told him that his only (slight) hope was continuous medication in the United States, that he must not engage in any other activity, and that he must remain hospitalised. Upon returning from Moscow, Fanon, in typical fashion, offered himself to the Algerian leadership as ambassador to Cuba!

The reason was clear: in Cuba, on 1 January 1959, the revolutionary movement led by Fidel and Che had taken power. With his great revolutionary insight, Fanon sensed that the revolution that was expected to squeeze imperialism was now becoming a transcontinental revolution. He was almost saying, ‘Hand me over to Dr. Ernesto Guevara, not to American doctors.’

In the end, he was convinced not to defy the laws of nature. In the second half of 1961, he agreed to be hospitalised in the United States.

The Wretched of the Earth

At the beginning of this article, we mentioned that Fanon's masterpiece, which has been in the hands of every revolutionary generation for the past 65 years, is a book titled The Wretched of the Earth. This book is a revolutionary manifesto, written by a man who felt death breathing down his neck, as if it were his last will and testament. We will not describe the book. It cannot be described; it must be read. Not because it is the best analysis of the world. In our opinion, The Wretched of the Earth is not a book; it is the cry of the black man, the ‘yellow race,’ the Indian homeless, and the fellah, all in unison throwing their misery into our ears.

Sartre wrote the following in his preface to the book, published in 1961:

‘They would do well to read Fanon: for he shows clearly that this irrepressible violence is neither sound and fury, nor the resurrection of savage instincts, nor even the effect of resentment; it is man recreating himself.’

In this book, Fanon defends an uncompromising revolutionary perspective. He argues that the re-humanisation of the native turned into a thing is impossible without violence. The doctor says this: if humanity is to be healed, this will only be possible through the ruthless destruction of the old world.

The author's tragedy unfolds like the final scenes of a thriller. Fanon wrote his masterpiece in March-April 1961. In Paris, the great revolutionary publisher François Maspero took it upon himself to publish the book, even though he knew the French government would confiscate it. Sartre willingly agreed to write the preface that Fanon had requested of him during their first and only encounter in Rome.

The book was released from the press towards the end of November. It reached Fanon, who was lying in a hospital bed in the United States, on 3 December. The package also contained Sartre's magnificent, glowing foreword to the book, as well as enthusiastic reviews that immediately appeared in the French press. Frantz Fanon passed away on 6 December 1961.

The meaning of Fanon in the 21st century

Today, post-colonialists and partisans of identity politics are inclined to have recourse to Fanon, as they have done with many other revolutionaries, as a prop for their own political framework, which constantly dabbles in “negotiations”. However, Fanon distinguishes himself from them in his political philosophy by linking the colonial revolution to violence. In other words, unlike identity politicians, he is a pure revolutionary. Furthermore, despite the progressive aspects of the movement of poets and artists known as ‘Négritude’, which included Aimé Césaire, Leopold Senghor, and others, Fanon explicitly rejected their approach, which glorified Africa's past and reduced African identity to a folkloric element.

Fanon is, above all, a revolutionary. He insists that the only consistent revolutionary force in the colonies is the poor peasantry. He opposes those intellectuals who wish to mediate between the coloniser and the colonised, thus advocating liberation through compromise with imperialism. He argues that they have attempted to hide their black skin behind white masks. Fanon is a Third World revolutionary, or, in the language more familiar to today's youth, a revolutionary of the ‘Global South.’

The title The Wretched of the Earth, despite all its poetic beauty, may not immediately mean much to those who do not speak French. This is because the term “wretched of the earth” (“les damnés de la terre”) appears in the first line of the original French version of the Internationale: thus the author seems to be referring to the global misery of a social class even more ‘cursed’ than the proletariat of the imperialist countries. Hence, whether in colonies or in imperialist countries, Fanon is a resolute enemy of reformism.

Fanon turned his face first to the African revolution, then to the general Colonial Revolution, escaping the trap of national or ethnic identity, and began to seek the re-humanisation of the colonised in universality. The answer to the problems he could not fully resolve lies in Che Guevara's Marxist internationalism, whose indispensable programmatic goal is world revolution. However, today's revolutionary Marxists must never forget that, at the dawn of the era of imperialism in early 20th century, Lenin updated, concretised and enriched the slogan ‘Workers of all countries, unite!’ placed by Marx and Engels in the last line of the Communist Manifesto: “Workers of all countries and oppressed peoples, unite!”

Frantz Fanon, alongside José Martí, Steve Biko, Hasan Ganafani, Malcolm X, and others, is a crucial example of the great revolutionaries who will march together with Marxists in the world revolution as the voice of the oppressed nations. These are the ones who do not begin with ‘Yes sir,’ but thunder forth directly with the words ‘No master!’ Fanon's story is their story.