We have just celebrated the 80th anniversary of May 9. We emphasized that the victory on May 9, 1945 proved that the antidote to fascist barbarism is not bourgeois liberalism and pacifism, but proletarian socialism. If Nazi Germany, and not the Soviet Union, had won the war, the last 80 years would have been a completely different period for humanity. Had Hitler been able to seize the Soviet colossus, enslaved the gigantic Soviet proletariat and started to exploit its underground riches, this might have finally opened the road to the defeat of Britain, and from there on, to wage war on America together with its ally Japan, all this opening the way to the reign of barbarism over the earth's face.

The war between the Wehrmacht, the army of Nazi Germany, and the Red Army, the army of the Soviet Union (hereafter abbreviated as the USSR), was in this respect not only a crucial turning point of the 20th century. IIn fact, it determined the future of humanity. Known in the United States and Europe as the "Eastern Front" of the Second World War (hereinafter abbreviated as WW2), and in the Soviet Union as the "Great Patriotic War", it has been described by some historians as the greatest war in history. When the Wehrmacht first invaded the USSR in 1941, its troop strength was 6.8 million. By 1944, this number had risen to 8 million. It is estimated that 30 million people died on the "Eastern Front" between 1941 and 1945. The total death toll of the WW2 used to be given as 60 million. On this basis, one could say that half of the deaths occurred on the Eastern Front. But, just as in the First World War (where the traditional figure was 10 million, yet today it is 20 million), in WW2 the figure has been rising, with 70 to 85 million casualties now being quoted. (The figures cited in this article are usually from Wikipedia.)

Returning to the Eastern Front, out of these 30 million, 5 million were Axis soldiers. That is, the soldiers of Nazi Germany and its allies (Italy, Romania, Hungary, etc.). This means that this war took the lives of 25 million Soviet citizens in 4 years. The number of civilian deaths goes up to 17 million. There are studies that calculate that 9 million of them were children. (In Netanyahu's Gaza genocide, out of the more than 50 thousand casualties on the palestinian side, 20 thousand were children, which clearly demonstrates the similarity between the Nazis and the Zionists.) The loss of the Red Army is estimated at 8 million.

Among these horrifying figures, the battle of Stalingrad occupies a special place. This battle, which took place between the second half of 1942 and the beginning of 1943, was the turning point of the war on the Eastern Front and was written in gold letters in history as testimony to the superhuman struggle of the Red Army and the Soviet people. These days, we are exchanging messages with our Russian communist friends and comrades to celebrate May 9th. As we were writing these lines, one of our friends (Saïd Gafourov) rightly wrote in his reply to our message of celebration that the "Great Patriotic War" was "an important milestone in the history of mankind". It has been said that the Eastern Front was eighty percent of the Second World War. The battle of Stalingrad was the decisive turning point in that war. It was fought by the Red Army and the working class of Stalingrad, factory by factory, house by house. A lone street resisted the onslaught of the Wehrmacht for weeks on end. The fate of humanity was determined by the working class, the Soviet society as a transitional society from capitalism to socialism under the rule of the workers' state established by the October revolution, and the Red Army built by Lenin and Trotsky, the founders of that workers' state. It was proletarian socialism that buried Hitler, the representative of the rabid imperialist bourgeoisie of the epoch of the decline of capitalism, in history.

Stalin's place in the victory

When discussing the Second World War, the "Great Patriotic War" and Stalingrad, one topic inevitably comes up. In recent decades, and especially after the collapse of the Soviet Union, Stalin's supporters, unable as before to attribute perfection to their great leader, have finally retreated into a defensive posture based on two basic facts. One is that Stalin was the architect of a major breakthrough in the establishment of socialism with planned industrialization and the collectivisation of agriculture. It is an undeniable fact that this "breakthrough" was based on, in the words of one historian, "stealing the clothes of the Left Opposition". Throughout the whole of the 1920s, apart from forcible collectivisation, which had never entered the programme of Marxism before Stalin, technological modernisation through the investment of the agricultural surplus in industry on the basis of central planning was the economic programme ardently defended by the Left Opposition, of which Trotsky was the leader. Against this, Bukharin, the theoretician of the right wing, advocated "socialism at snail's pace", and Stalin hid behind him. When there was a huge grain delivery crisis in 1928-1929, Stalin took this program of the Left Opposition and added to it the forcible collectivization of agriculture. It is well-known that in the process of forced collectivization, millions of people starved to death, livestock was rapidly decimated, and the peasantry in many regions (most notably in Ukraine) and the tribal nomads in Kazakhstan began to join opposition movements, even movements with fascist tendencies. But in the end, the indisputable superiority of the planned economy in the modern era made it possible for the USSR to rapidly industrialize and make a breakthrough in armaments and military technology.

The second point to which his followers clung in defence of Stalin was the USSR's defeat of Nazi Germany. We will not deal with economic policy in this article. We have done that elsewhere. The second volume of our book Marksists (in Turkish) is the first source we can point to on this subject. In the Turkis edition of our theoretical journal Revolutionary Marxism, especially in the run-up to the 100th anniversary of the October revolution, several of our comrades have dealt with this issue in depth. We plan to address some other aspects of this issue in the future that we have not yet written about.

The question we will address in this article is Stalin's role in the war. Yes, the USSR and the Red Army played a central role in the defeat of Nazism. That is true. But does it follow that Stalin was a great historical leader? What was Stalin's role in the victory? This is the question we will seek to answer.

Stalin's lack of foresight

Politics is based on foresight. If you fail to see the trend of events clearly and accurately, you will not be adequately prepared for future opportunities and threats and will have to pay the price. This was precisely the fate of the "Great Patriotic War". Far from being able to foresee that Hitler would invade the USSR, Stalin shut his ears to all the warnings of the Soviet state and even of actors from other countries, thus placing the workers' state in grave danger.

It is widely known that the USSR and Nazi Germany signed a pact in mid-1939. This pact, commonly known as the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact after the names of the foreign ministers of the two countries, restored the political status of various parts of Eastern Europe to the pre-World War I status quo ante. It was on the basis of this pact that Stalin dogmatically clung to the idea that Hitler would not attack the USSR.

This was based on the idea that Hitler could not afford to fight on two fronts. Hitler had invaded many countries in the West, notably France, using Blitzkrieg tactics. But Britain had proved to be a tough nut to crack. According to Stalin, the Nazis could not attack the USSR without first conquering Britain. Stalin was constantly referring to the possibility of Hitler being provoked by a wrong attitude. So there was no danger unless Hitler got pissed off and a pretext was created for him to attack the USSR.

Worse still, the complacency that was the product of this viewpoint, based on the absoluteisation of a single factor (fighting on two fronts), persisted despite warnings to the contrary from many sources. For example, he received 80 warnings in the eight months before the Nazis attacked, but dismissed them as invalid (Beevor). In fact, the Soviet state, like all sane states, had an extensive network of spies in capitalist countries. These included the Red Orchestra, a network in Western Europe run by a Polish communist named Leopold Trepper, and Richard Sorge, based in Japan, whose information indicated that Germany had long been preparing for an attack (Trepper). There were also reports from Britain, Sweden and the Lucy spy network in Switzerland, set up by German Nazi opponents. Stalin called it all a "British trap", indicating that Britain was seeking to pit Hitler and Stalin against each other and thus erode the strength of both enemies, and also to secure itself by driving Hitler eastwards. This reasoning was not implausible. Indeed, after the Nazi-Soviet war began, Britain and America practiced the tactic of attrition on both sides with remarkable transparency. The problem is that this reasoning was adopted as if there were no other alternative, and Stalin dogmatically defended this view. If a state believes that its entire intelligence network is full of idiots or traitors, it is doomed to lose.

After the start of the war, Stalin openly admitted to the special envoy of the American President Roosevelt that he had not expected an attack and had been caught unawares (Deutscher).

"One of the biggest defeats in history"

Lack of foresight and stubbornness in such a strategic matter will surely exact a price. For one thing, Stalin admitted before history what a big mistake he had made with his abnormal behavior at the beginning of the war. On June 22, 1941, Hitler's armies entered the territory of the USSR in three flanks with a gigantic invasion force (6.8 million troops, we said above). For the next 15 days the Soviet people did not hear a word of explanation from their "great leader". Stalin, who completely locked himself up on the first day, later held meetings with his General Staff, but was unable to address the people (not even in a radio address)! (Deutscher)

While he was hiding from the people, the Nazi army (Wehrmacht) advanced 700 kilometers into Soviet territory in one month. Again it was Stalin who was responsible for this. The earlier instruction " do not give in to provocations" had been transmitted to the units as the main directive on 22 June. The planes of the Red Air Force were therefore to be largely destroyed while lined up at airfields waiting for their assignments!

The Nazi army would advance rapidly and take Kiev, paralyze Leningrad (today St. Petersburg) in the course of a 900-day siege, launch a powerful siege to conquer the capital Moscow, march into the oil-rich Caucasus, and in the meantime arrive in front of Stalingrad in the Volga region. By the end of 1941, in just six months, the Red Army had lost 4 million men! Geoffrey Roberts, one of the most important military historians of WW2, describes the period of the years 1941-42 as "one of the greatest defeats suffered by any army in history." (Roberts)

4 million! Six months!

Shouldn't the Stalinists be a little humbler, a little more restrained?

The bigger picture as the Nazi offensive begins

What was the state of the Red Army when the Wehrmacht, arguably one of the most powerful armies in history (modern history too), invaded the USSR?

Historians of this war, including Georgi Zhukov, who was made Deputy Supreme Commander-in-Chief by Commander-in-Chief Stalin from 1942 onwards and is rightly recognized as the greatest military leader of the "Great Patriotic War" , write that the Red Army was in a miserable state at the beginning of the war, but that things improved as the war went on (Zhukov does so in his autobiography).

The situation was this. Officers and non-commissioned officers were both understaffed and inexperienced. The soldiers had little training, and since the need for conscripts increased rapidly after the occupation began, young men recruited during mobilization were sent to the front after ten days of training. Peasant youth recruited from collective farms had a low level of education and were ignorant of military technology and modern weaponry. (Beevor)

Since planned industrialisation had enabled the USSR to make a great leap forward in terms of weapons and military equipment, the army was incomparably more advanced in this respect than before. What, then, was behind this pathetic state of affairs in terms of the human element?

The Great Purge, the most important phase of the rise to pwer of the bureaucracy in the USSR, which purged the party of Bolsheviks and eliminated the leadership of the October revolution, could not help but crush the army as well. The military Great Purge, which began in 1937, was not unlike the political campaign, which though was of course was broader in its scale and scope. Thirty-seven thousand of the Red Army's officers were to be imprisoned or discharged if they were lucky enough not to be executed. Of the 706 officers in positions above the rank of brigade commander, only 303 would be spared. (Beevor)

During the Civil War (1918-1923), the Red Army had become the darling of the country. We are talking about an army that won the war although 80 per cent of the country had earlier fallen under the occupation of the imperialists. It was thanks to the Red Army (and the Red Navy, the Red Air Force etc.) that the workers were spared from losing their soviets, the peasants from losing their newly won land, and the country from losing its independence. Only 14 years later, the Red Army, the hero of the working class and peasantry, was declared by the Party Central Committee, in fact by Stalin himself, to be a criminal network full of enemies, spies, subversive elements, etc.!

Since among those executed were the heroes of the Civil War, close comrades-in-arms of Commander-in-Chief Trotsky, everything made sense. In the military as in the political sphere, Stalin was purging Bolsheviks who were in danger (!) of succumbing to the dream of "world revolution". Among them was Marshal Mikhail Nikolayevich Tukhachevsky, who had become famed as the "Red Napoleon". On the occasion of the defeat of the Red Army under Tukhachevsky's command near Warsaw in 1920, Stalin and Tukhachevsky had a sharp confrontation. Stalin later would take to disdainfully referring to him as "Napoleonchik" (Little Napoleon), since the nickname "Red Napoleon" glorified him. In the 1930s, Tukhachevsky was First Deputy Minister of Defense, while Stalin's man Voroshilov held the post of Commissar (equivalent of minister). It is widely believed that Voroshilov was instrumental in making his deputy the target of a plot to execute him. Tukhachevsky not only paid careful attention to the technological modernisation of the Red Army, the development of the air force, and modern methods of inter-unit communication, but he is also seen as the inventor of the military doctrine known as "deep operation". This doctrine is sometimes also known as "mobile war and operational art" or "armoured blitzkrieg". The emphasis is on striking and dispersing the enemy with different types of military vehicles and striking power at deep ranges behind enemy lines.

In the field of military doctrine, Tukhachevsky's doctrine suffered an eclipse with his execution, as happened to others in the field of science, philosophy and theory. But when Zhukov used this doctrine with great success at the start of WW2 in the fall of 1939, in the Khalkin-Gol battle with Japan in East Asia, he achieved a great victory and with it the glory that would later elevate him to Deputy Supreme Commander. While the doctrine was pushed underground, so to speak, because Tukhachevsky was demonized, it was skillfully used by commanders Zhukov and Vassilevsky to launch a counterattack in Operation Uranus, which played a major role in winning the battle of Stalingrad, and was written in gold letters in the history of warfare. (Beevor)

It was thanks to such commanders like Zhukov, Vassilevsky, Rokossovsky, who was excommunicated in the past but became a hero during the Nazi invasion, by being brought out of the hole he was locked in, and Rodion Malinovsky, who sincerely put themselves forward to win the war against Nazism, who took risks, and who clung to the historical traditions of the Red Army, that the Red Army, which had initially crumbled, recovered in time. Under Zhukov's command, after the Battle of Stalingrad was won, the fate of the war would change, and from that point on, the Red Army would drive the Nazi aggressors all the way to Berlin and bring Nazism to its knees before history with the Unconditional Surrender Agreement signed on May 8-9.

Before concluding, let us briefly mention how Zhukov deals with the 1937 purge in his autobiography. Zhukov begins as follows:

The commanders of the majority of military districts and navies, members of military councils, corps commanders, commanders and commissars of troops and units were arrested. Honest employees of the state security organizations were also arrested. There was a terrible atmosphere in the country. No one trusted anyone, people were afraid of each other, avoided conversation, did not want to speak in front of third parties. There was an unprecedented epidemic of slander. Honest people were sometimes slandered by their closest friends. Because everyone was afraid of being suspected of being unfaithful.

Zhukov talks about the 1937 purge for pages. He says that his own dossier was being prepared and that the turning point that saved him was being sent as a commander to Khalkin Gol. Even though he was publishing his memoirs during the thaw period after Stalin's death, the so-called "destalinization" period, the censors removed all this from the book. Only two or three sentences remained. One sentence about "baseless arrests in the armed forces that violate socialist legality". And this sentence: "Leading commanders were arrested. This naturally affected the development and operational readiness of our armed forces." What better witness than the heroic Deputy Commander-in-Chief? And how do we learn about the censored passages? Zhukov's youngest daughter Maria, in fulfilment of her father's will (Zhukov was to die in 1974), kept the manuscript and had the unpublished sections published in the 10th and 11th editions after the dissolution of the Soviet Union. (Zhukov)

What did the Soviet Union lose while winning the war?

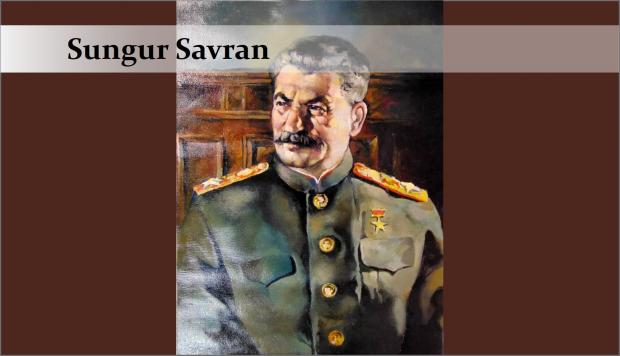

Before reading this section, we advise the reader to look again at the photograph at the beginning of this article. Therein lies the key to understanding the issues we will now discuss.

Stalin's methods of liberating the Soviet country from the threat of WW2 were, of course, not purely military. Quite the contrary. In this period, his stragey was to bring about changes that would undermine the most fundamental founding principles of society, that would profoundly affect class relations, that would cause the greatest shocks to the class character of the October revolution in the cultural sphere, and that would open up space for nationalism and religion in the ideological sphere. Let us go over them quickly.

For one thing, in terms of the organization and internal relations of the army, the outstanding regime brought about by the October revolution collapsed. The Red Army had had to recruit commanders of the Tsarist Army when it was first formed. This necessitated the appointment of party commissars to each unit in addition to tje commander. In 1942, the rule of appointing a commissar to each unit in addition to the commander was abolished, since. Thus, one of the safeguards of the army's commitment to socialist policies was removed. Far more important was the return of the army to the caste system of the armies of traditional class society at the beginning of 1943. In Lenin's and Trotsky's Red Army there was neither the soldier's salute to the officer, nor epaulettes, nor discrimination between officers and non-commissioned officers in their places of rest and recreation (officers' clubs). The epaulette has made a "magnificent" comeback! It is now not only a necessity to wear epaulettes, but it has also become customary to embellish them with tassels and polish them with a gold base.

Now take another look at the above photograph of Marshal Iosif Vissarianovich Stalin. The Stalinist, rejoicing and feeling proud over this photograph, lives in the illusion that Stalin is the continuation of Lenin, not even noticing that under Lenin there was none of this, that the commander and the privates were each other's comrades, that under Stalin the Commander-in-Chief wore epaulettes with tassels and gold braids, while Lenin's Commander-in-Chief, Trotsky, wore an extremely plain uniform, without epaulettes. The Stalinist's class consciousness does not allow him or her to realise anything more, because he or she is a supporter of the bureaucracy, which itself has the character of a caste. If his or her consciousness were enough to recognize the difference between the world views of Lenin and Stalin, then he or she would not be a Stalinist at all.

How much more has changed during the war! In order not to bog down a long article with more details, let us briefly mention the following. The Orthodox Church was revived and the way was paved for religious propaganda ın the ideological sphere. The old Russian "heroes" who were vilified during the October Revolution, such as Aleksandr Suvorov, the "invincible commander" of the 18th century or Mikhail Kutuzov, who resisted Napoleon in the 19th century, were again deemed worthy of heroic honours. The Order of Suvorov and the Order of Kutuzov, created in their names, were worn on the chest of Soviet officers as a badge of shame. Tsarist and Soviet commanders shoulder to shoulder against fascism!

In line with this, Russian nationalism was once again legitimized. Stalin claimed that Nazis should not be referred to as nationalists, but rather as imperialists. In this way, an attempt was clearly being made to lend respectability to nationalism, which for Lenin was entirely outside the framework of Marxism. As a result, while the anthem of the Soviet Union had previously been "The Internationale"—the legacy of the Paris Commune and the indispensable anthem of international proletarian socialism—Stalin replaced it with a Russian anthem. The first line of this anthem is essentially the creed of Stalin's revenge on Lenin: “Great Russia has established the indivisible union of free republics forever…”

We elaborated extensively on the internationalist significance of the great struggle Lenin waged at the end of his life to get the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics accepted in our book Lenin: Leader of the World Revolution. As we can see, Stalin could not abolish the guarantees the USSR provided to small and subordinate nations, but at an ideological level, he glorified nationalism by instilling loyalty to “Great Russia” in every Soviet youth—at every national match, every week in school, during military service, and in many other contexts.

And notice: “free republics,” but an “indivisible union”! In what sense are these republics free, one might wonder.

Of course, if the goal of your “socialism in one country” is the indivisible unity of “Great Russia,” then the International becomes unnecessary, and the Communist International turns into an obstacle. Stalin dissolved the International, which Lenin had founded after a quarter-century of struggle, during the middle of the war without even calling a congress, purely by personal decision! This was the height of betrayal of communism—whose program was world socialist revolution—and its most advanced form, Leninism. (All of this is discussed in detail in the second volume of our book titled The Test of Socialism with Internationalism.)

In this context, it becomes clear that for Stalin, the war against the Nazis truly was the “Great Patriotic War.” This term was derived in the early days of the Nazi invasion from the “Patriotic War” used during Napoleon’s 19th-century campaign against Russia—with the addition of “Great.” The class basis of the war disappeared here. But during the days of Lenin and Trotsky, the Red Army was a class army. It was built through class methods; its oath was a class oath. During the Civil War, its goal was to defend the workers' state marching on the path of world revolution. A quarter-century later, we see that the aim of class struggle had completely vanished from the agenda.

Soviet workers won the “Great Patriotic War” but lost many of the safeguards of Lenin’ workers’ state. Anyone who cannot see the roots of the 1991 collapse here should definitely see an eye do

Stalin’s Limits

Some, instead of understanding and criticizing Stalin's historical role, let themselves be ruled by anger, prejudice, or even the arrogance of their privileged intellectual status, developing outlandish arguments. Some mock his background as the son of a poor shoemaker and as someone educated in a religious school, akin to an Imam Hatip in Turkey. Others, contrasting him with cosmopolitan figures like Trotsky or with Bolshevik theorists like Bukharin, find him overly Asiatic, despotic, or crude. Some think he was stupid or mock him for being theoretically weak.

We do not view the world through upper-class prejudices, but with an effort to remain faithful to the perspective of the worker and laborer. This perspective allows us not only to see the flaws of our adversaries but also to understand their strengths. When someone succeeds, we try to understand why they succeeded. We do not simply say, “It happened—who cares why?”

Stalin became an immensely powerful leader at the top of the Soviet state in the 1920s and 1930s with the support of a rising bureaucracy, eliminating all potential strong rivals. To have done this—even by vile means—he must have had some abilities. The Stalin–Trotsky debate is not about who was more brilliant, smarter, or better-informed. Such an approach should be rejected, even condemned, because it reflects Eurocentric and class-biased evaluations.

Trotsky’s superiority as a theorist compared to Stalin is not insignificant. But politics is not just theory. Trotsky was a better theorist than not only Stalin but also Bukharin, Preobrazhensky, and others. He may have been one of the 20th century’s greatest orators—when he spoke with “a voice like a bell,” as Nazım Hikmet said, crowds would fall silent and listen. Stalin, in contrast, was a dull and insecure speaker of short sentences. But politics cannot be reduced to oratory. And more importantly, linking political effectiveness to someone’s education or national origin is wrong and un-Marxist.

Let’s now tie this to the subject of the article. Stalin may have betrayed Marxism and the revolution. But did he play a positive role in defending the Soviet Union against the Nazis, who had surrounded it like a pack of wild beasts? Did he contribute in this way?

We are neither experts in the art of war nor claim to have mastered every detail of Soviet history, despite our careful study. But the analyses of Isaac Deutscher and Georgi Zhukov—who had no political, theoretical, or personal connection—often align, and seem reasonable to us. We will attempt to relay this as a provisional evaluation.

The first point is this: Despite making major military mistakes, Stalin achieved important political-strategic successes in the war. We do not overlook the major strategic misjudgments before the Nazi invasion—like the belief that Hitler would not fight on two fronts. But once the war began, the political decisions underpinning military operations became integral to strategy.

In light of the 1941–1942 disaster, Stalin made a crucial strategic decision by relocating factories, industrial stockpiles, and agricultural yields to the east of the country. Similarly, relocating ministries and government offices from Moscow to eastern settlements proved prescient when Moscow nearly fell. Most importantly, despite this evacuation, Stalin and the top command chose to stay in Moscow—a city where even the Central Committee meetings were held underground in the Mayakovsky Metro station.

The psychological impact was huge: the evacuation of the state apparatus gave the people the impression that Moscow was being abandoned to Hitler. But Stalin’s decision to stay calmed looting and boosted morale among the anti-fascist public. In the eyes of the Soviet people, Stalin appeared as the selfless protector of the country.

The second point, emphasized by Deutscher, is that Stalin was more capable and eager in strategic planning than in operational military decisions. Unlike Trotsky, who traveled across the vast Soviet terrain during the Civil War to assess front-line conditions and inspire troops under fire, Stalin remained in the Kremlin, consulting commanders and making decisions through a kind of “military polling.”

His contribution to the USSR’s survival seems to evaporate beyond this point. Stalin never became the military genius his supporters have claimed. Zhukov asserts that Stalin was well aware of his operational weaknesses. When Stalin offered Zhukov the position of Deputy Commander-in-Chief and Zhukov declined, saying “we won’t get along,” Stalin responded by saying, “Let’s rise above our personalities.”

Zhukov’s harsh judgment: “By the end of the war, his grasp wasn’t too bad.” The best that can be said of a leader who directed the war for years is: “not too bad.”

Deutscher also notes that Stalin often consulted various commanders and adopted whatever majority opinion emerged—thus avoiding mistakes while making it seem like the decision was his own. But Stalin had another great sin: he envied successful commanders, fearing they might become rivals in peacetime. Consequently, he obstructed the most talented officers.

After the war, even Zhukov, Malinovsky, and Konev—whom Zhukov said had always been jealous of him—were sidelined by Stalin. Earlier, Stalin had relied on generals like Voroshilov and Budienni, whom Trotsky mockingly called “sergeants.” Their disastrous performance in early stages of the war forced even Stalin to remove them and promote more capable commanders like Zhukov, Vasilevsky, and Rokossovsky.

Who is the Hero?

The article’s title is “Who is the True Hero of the ‘Great Patriotic War’?” and the photo points to Stalin. Some readers might, upon first glance, exclaim, “Has Sungur Savran capitulated to Stalinism?”

But after this long analysis, we now understand that Stalin is not the hero. So who is?

Let’s leave it to others' testimony with a few short quotes:

June 22, 1941 – While Stalin remained silent, Foreign Minister Molotov addressed the Soviet people. After the speech:

A female student recalled, “It felt like a bomb fell from the sky—the speech had that kind of shock effect.” She immediately volunteered as a nurse. Her friends, especially Komsomol members, started collecting money for the war. Reservists rushed to enlist before the draft call. Within 30 minutes, reserve soldier Viktor Goncharov left his house with his elderly father, assuming he was there to see him off. But his 81-year-old father, who had fought in four wars, had come to enlist with him. When rejected, the old man flew into a rage. (Beevor)

The situation of the rank-and-file soldiers:

The Germans’ biggest mistake was underestimating “Ivan”—the ordinary Red Army soldier. They quickly discovered that Soviet soldiers would fight on even when surrounded or vastly outnumbered—situations where Western troops would surrender. From the first day of Operation Barbarossa, countless acts of bravery and sacrifice occurred. (Beevor)

General Blumentritt, Deputy Chief of the German General Staff, during the siege of Moscow:

“Some units of our 258th Infantry Division entered Moscow’s outskirts. But Russian workers rushed out of factories, defending the city with hammers and other tools.” (Deutscher)

In Stalingrad, workers from local factories joined Chuikov’s 62nd Army—including veterans who had fought under Stalin and Voroshilov 22 years earlier during the Civil War. (Deutscher)

Why? Why did these people—who had endured war, hunger, poverty, and oppression—fight with such selflessness?

Again, let’s hear from Beevor. Elite Guard Regiments were known for their prestige and pomp. A soldier in one of these regiments heard from a shoeshiner at a train station:

“They’re bringing back epaulets again,” the man said bitterly, “Just like the White Army.” When the soldier told his comrades, they were stunned: “Why would the Red Army do this?”

When a worker, peasant, or even a solitary shoeshiner asks such questions, the working class embraces their country—no matter the hardships. And when they do, they fight like no other, because they’re not only defending their homeland, but also their jobs, bread, families, and children.